Forecasting 101

Every SaaS founder and CFO must forecast their finances—these are our best practices for getting ahead of uncertainty.

Startup founders and CFOs know that winging it isn’t a winning strategy. Once you’ve built a budget for the year, it’s time to start forecasting. Founders can get started from day one, and the right finance leader can build a team that models the impact of all kinds of possible business scenarios.

“There’s no scenario where you present a forecast without identifying possible risks and opportunities,” said Elena Gomez, CFO of Toast.

Whether you’re thinking about expanding into a new geography, launching a new product line, or trying to ensure you’re on track toward your profit target, forecasting the next month, quarter, and year can make new terrain can make an unknown horizon feel more certain.

But how is forecasting different from budgeting, and what does it take to start doing it on a regular basis?

On Atlas, we talked with five experts in SaaS forecasting––Elena Gomez, CFO of Toast; Meena Srinivasan, fractional CFO at Tia; Rami Essaid, co-founder and CEO of Finmark; David Appel, Global Head of the Subscription and SaaS Vertical at Sage Intacct; and Jeff Epstein, Operating Partner at Bessemer Venture Partners––about how founders and finance leaders should go about building forecasts, from the earliest to public-readiness stages.

What is forecasting?

Forecasting prepares business leaders for uncertainty––it’s the practice of using historical data to make informed predictions of future income and expenses, based on different possible scenarios. It’s not to be confused with budgeting, though. Forecasts are regularly updated, whereas budgets are not.

“If you have to commit yourself to a revenue or cash flow figure and are unsure how you’ll achieve it, every founder knows that’s a horrible feeling," said David Appel, Global Head of the Subscription and SaaS Vertical at Sage Intacct. "But you don’t have to feel that way, which is where different levels of forecasting come into play.”

“Forecasting is often a lighter version of budgeting,” explained Jeff Epstein, operating partner at Bessemer Venture Partners. “In normal circumstances, you can create a detailed revenue forecast weekly or monthly. In contrast, since it’s usually easier to forecast expenses, you can forecast expenses at a higher level, based on variances from your budget.”

“Forecasting is like climbing a mountain—even when you have done everything to prepare and plan, conditions keep changing and avalanches can threaten to knock you off your course,” said Meena Srinivasan, fractional CFO at Tia and former CFO of Ginger (now Headspace Health). “As long as you are constantly looking out for changing conditions, you can course-correct without wavering on your destination.”

The nuts and bolts of a company's forecast depend on the maturity of the business. In the early stages, founders might forecast cash inflows and outflows––though it should eventually cover the full profit and loss (P&L) statement, bookings, and other key metrics, explained Meena.

Forecasting can also explain key parts of a company’s business model, such as price per unit and annual contract value (ACV), explained Rami Essaid, CEO and co-founder of Finmark.

Forecasting brings a nascent business model to life

Forecasting helps early-stage founders envision a realistic future for their ever-changing business.

Founders who are forecasting for the first time might fear missing the mark with their initial attempt, especially if they don’t have a strong finance background. “Building your first forecast isn’t about getting it right––it’s more about getting your ideas down on paper,” explained Rami.

The first few forecasts can help bring a nascent business model to life, Rami added. “I recommend people do some form of forecasting when they’re first coming up with a business model,” said Rami. “When you’re coming up with a product, you have to estimate how much it’ll cost you to turn your minimum viable product (MVP) into an initial product, how many employees you’ll need, and how much runway you’ll need. Those questions come with basic assumptions, such as price per unit or annual contract value (ACV), which can lay the groundwork for a forecast.”

In addition to building a forward-looking view of a business model, forecasting can help founders make decisions about the amounts of capital and resources to commit to new products and initiatives. That’s especially true of hardware: consumer electronics companies that notice an increase in demand at certain times of the year, like the holidays, can use this information to build more inventory, explained Meena. That’s to help prevent shortages or overstocking, which could lead to financial losses. But for hardware and software companies alike, strong forecasting can help business leaders determine the right amount of risk to take with their cash position, she added.

FP&A typically builds forecasts

In the earliest stages of company-building, founders are tasked with overseeing financial planning activities, such as budgeting and forecasting. Eventually, forecasting falls under the purview of a company’s first finance hire, who typically builds and revises financial models.

Initial financial planning support might look like a combination of software and external consultants or fractional finance leaders, but eventually it’s important to bring on a full-time hire who’s steeped in the day-to-day operations of the business. “You want to hire someone who understands the business well enough to adjust the variables,” said David.

Finance leaders tend to agree that the right time to hire someone to build forecasts full-time is when the business grows in complexity.

Many finance professionals also encourage founders to learn about the differences between accounting and financial planning and analysis (FP&A) experts. “It’s a lot like sports, where there’s a play-by-play commentator and a color commentator,” said Elena Gomez, CFO at Toast. “The person who tells you what happened play-by-play is the accountant, and the color commentator who explains the forecast and future trends is FP&A. I think you need both.”

How often founders should build forecasts

“It’s never too early to start forecasting, and it’s especially critical in today’s unpredictable economic environment,” said Meena. “Even if you’re in the very early stages, I think it’s helpful to ask, ‘How are we tracking to our milestones? Do we need to course-correct?’”

“Forecasts are estimates, not crystal balls,” Meena added. “Whenever your outlook changes, you should update your forecasting assumptions to see exactly what the impact would be to your finances.”

The right forecasting cadence is tied to how quickly things change in your business, said Meena. “If your business is very dynamic, then it’s important to update your forecasts very frequently, say weekly or monthly,” she added. “On the other hand, if you have a fairly steady and predictable business, quarterly forecasting is sufficient.”

Still, in some cases it makes sense to make even more frequent forecast updates. “I’ve worked at companies where you want to be looking at weekly, or even daily metrics underlying the business, to answer the question, ‘What’s happening in the field today, right now?’ added Elena. “In a business like ours where payment volume is part of the revenue stream, we may want to know the latest data on a daily or weekly basis. But if SaaS revenue is the only element of the business, and at businesses with longer sales cycles and those without usage-based pricing, you could probably live with weekly or monthly forecast updates.”

“I think a model has a half-life of about one month, meaning that every month that goes by, its accuracy decays by 50%,” added Rami. “If you don’t regularly update it, it’s not going to provide an accurate forecast of the future.”

Later-stage companies preparing for the public markets can benefit from preparing quarterly forecasts ahead of time, since it’s a process that takes getting used to, added Elena.

Finally, forecasts help companies adjust to new realities throughout the fiscal year. While the company budget typically doesn’t change, business leaders have to modulate their spend based on what they’re seeing in the forecast, said Meena.

The forecasting tech stack

Finance teams often use Excel to build forecast models, and separate enterprise-grade software to share the final model with leaders throughout the company, who might use the agreed-upon model and recent data to conduct budget variance analysis, said Elena.

Earlier-stage companies looking for their first FP&A tool beyond Excel might consider software like Finmark or Jirav, while larger enterprises might use Workday Adaptive Planning or Anaplan.

Tactical advice: How to build forecasts

According to Elena Gomez, CFO at Toast, founders and finance leaders looking to build forecasts should ask these three questions:

- What is the goal? Zoom out to the bigger picture as a starting point. What is the high-level objective––is it reaching a certain top-line revenue target, posting a profit, or something else?

- What are the underlying drivers of actual results? Lean on historical financial data to plan for the future, but take things one step further by thinking critically about the factors driving the data––whether that’s the macroeconomic climate, post-COVID-19 pandemic challenges, or industry-specific conditions (e.g., restaurants, hospitality, etc.)

- What possible scenarios do you have in mind? In addition to determining the most likely scenario, it’s important for founders and finance leaders to anticipate what an upside or downside scenario might look like, and the possible drivers behind them.

On a tactical level, Rami Essaid of Finmark encourages founders to follow these five steps to build a forecast:

- Collect and visualize historical financial data from the past six to 12 months.

- For flat or steady line items, assume it’ll remain consistent, and roll that forward.

- For variable line items, assess why they’re changing.

- Understand the company’s main revenue drivers, and decide how aggressively the business can lean into those drivers over the period that’s being forecasted.

- Understand the inputs associated with each revenue driver.

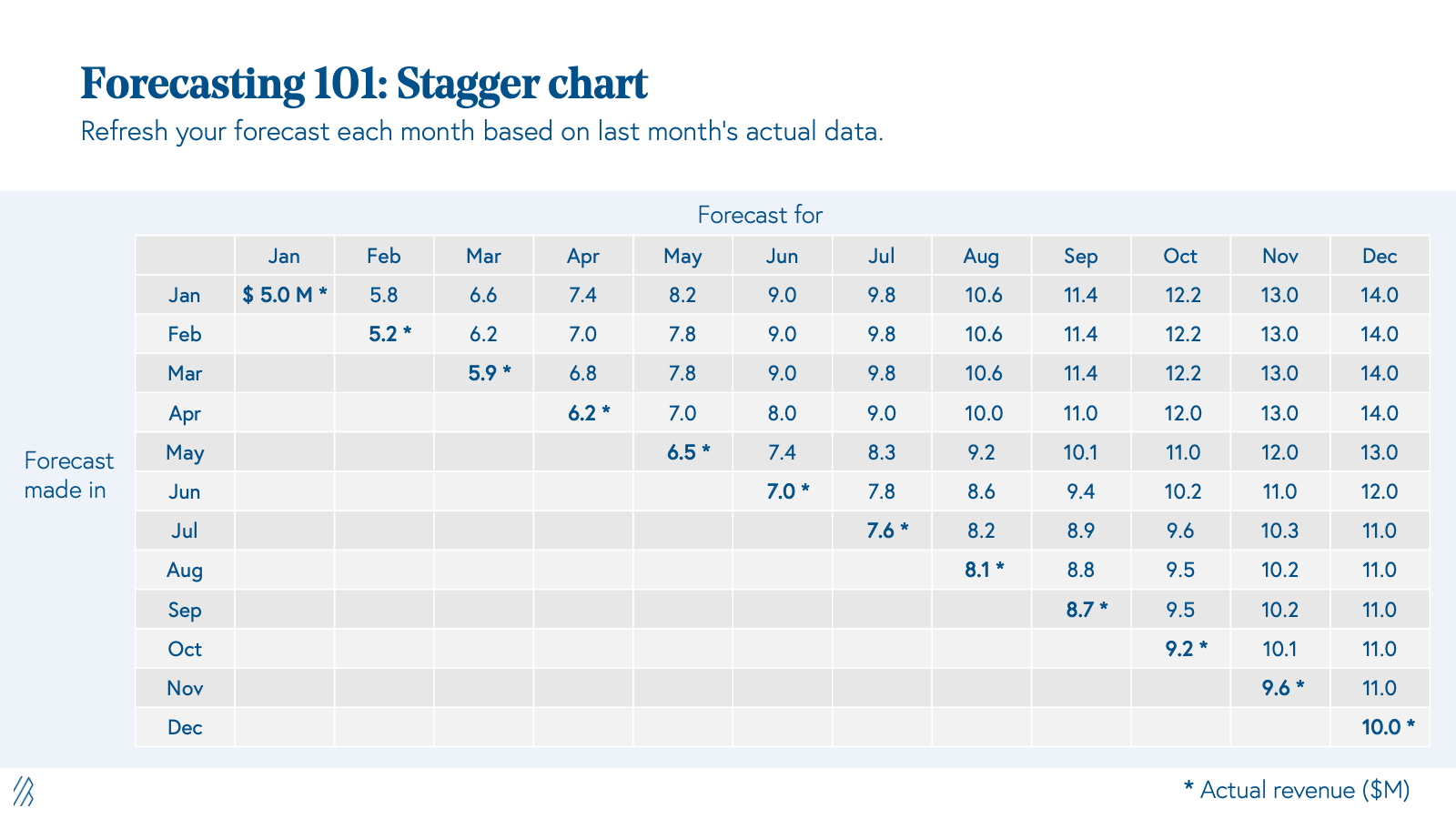

To illustrate an example of how forecasts can change on a month-by-month basis, Bessemer’s Jeff Epstein recommends that companies build a stagger chart, based on the idea in Andy Grove’s book High Output Management. The idea behind a stagger chart is to revise the remaining forecast based on each new month of actual data.

The best-prepared companies build more than a single forecast––that’s to anticipate different possible business scenarios. Scenario models can consider possibilities such as:

- What if my demand is X? What if my demand is X + 50%?

- How would it affect the bottom line if we invested more in one product line versus another?

- For services businesses, how much personnel would be needed at different levels of customer usage? (e.g. number of net new therapists a mental wellness platform would need per X new signups)

“One scenario founders may want to plan for is having a board plan and a more aggressive management plan,” said Elena. This ensures you have room to always hit the board plan and also ensures the management team has an aggressive but achievable plan. It’s not uncommon for companies to have a management forecast that has a 5-10% delta from the board plan figures.”

Elena and Meena agree that the forecasting process is incomplete without qualitative information as context. “The texture underneath the forecast is as important as the forecast itself,” said Elena. Take the case of a company that makes an assumption about the attach rate of a product launch in a new region––if the attach rate turns out to be better than expected, and that region doesn’t have a strong sales presence, the right forecasts could justify a conversation about the pros and cons of investing in sales headcount in that region.

“There’s a huge qualitative element to forecasting, because the more you understand the business, its products, the market, the customer base, and the way it operates, the better you will get at forecasting your business,” said Meena. “You have to understand what's going on at a deeper level to be able to forecast more accurately.”

To put this wisdom into practice, Meena encourages founders and finance leaders to derive insights from actual financial results and historical data to make more informed business decisions. “Across your team, if everyone is achieving 30% to 50% of your sales quota, it could mean that the sales quotas are unrealistic or do not reflect the current market situation.”

Parting wisdom—the importance of flexibility when tackling common challenges in forecasting

Now that our experts have shared the fundamental advice for founders, Elena leaves us with five important lessons for founders to keep in mind during the forecasting process.

- Don’t focus on too many levers. “One thing I have seen founders get wrong is a focus on too many levers,” said Elena. “Typically, you can boil it down to three or four levers that are the real needle-movers. Don’t over-rotate on all the things, because if you do, you’ll get lost in the noise.”

- Learn from the past. “If you materially missed the prior month, really understand the ‘why,’ not just the ‘what,’” added Elena.

- Get input from different stakeholders. Sharing your scenarios with key stakeholders and walking them through your version of what the levers are is really powerful, Elena said. It also helps to be able to point to the accountable business leader.

- Forecast different models for different parts of the business. For example, a SaaS company might have a recurring revenue model to project its primary revenue stream, in addition to a different model for the professional services part of that business. And within a revenue model, it might make sense to make models for different customer segments within the same business if they tend to behave differently.

- Build in contingencies for what could go wrong. Think of your forecast along the lines of an investment portfolio, suggested Elena––some parts of the business won’t perform as well as others, so it’s important to hedge the aggregate model a bit, even as little as 5%.

Elena’s suggestions highlight a critical habit of mind of savvy financial analysts and operators: the ability to outsmart optimism bias. A common cognitive bias, humans tend to overestimate the likelihood that positive events will unfold. (That’s especially true in business––think about how many capital investment projects finish later than planned and over budget.) With this in mind, while forecasting, founders should add buffers or ranges to their plans; that way, management teams can aim for their ambitious goals while also knowing the reasonable time and money bounds in which they need to achieve them. As Elena speaks to the importance of building in contingencies, even financial forecasting requires a degree of flexibility.