Training: The power of movement and how a physical regimen keeps leaders sharp

Physical fitness is crucial for demanding executive routines, providing enhanced focus, increased willpower, and resilience.

Physical exercise and caring for our body through movement or training are some of the largest determinants of our lifespan, and also of our healthspan, which is arguably just as important — that’s the amount of life you live in good health, free of chronic disease and the disabilities of aging. Said another way, it’s the amount of life you’re able to enjoy.

But of course, physical health is intrinsically linked with mental health, too, and in this chapter, we’ll discuss how they are deeply interrelated. Exercising your body exercises your brain. It helps you form willpower and self-control. It increases your ability to withstand challenges — just ask any athlete.

We’ll also explore recent science that overturns long-held wisdom. Did you know people living in hunter-gatherer conditions don’t lose strength as they age? They also don’t suffer cardiovascular disease, nor become as prematurely enfeebled as people do in Western societies — a condition known as “sarcopenia,” the loss of muscle mass. In a way, we’ve gotten it all wrong. Old age doesn’t cause us to move less — moving less causes us to age.

So as a corporate leader, how can you build an optimal regimen for a life where you’re as busy as you are with work? We’ll recommend thinking about your training regimen on two speeds: Maintenance or being active daily, like our hunter-gatherer friends who continue to walk the same distances well into their 70s, and performance, or being able to push yourself to your peak.

We’ll discuss the science of exercise, the components of a healthy, sustainable executive regimen, and ways some people finally make that routine stick so they don’t get stuck.

TLDR on training

Physical training is the largest determinant of your lifespan and your healthspan — the amount of your life you stay healthy and active. Consider two motions. The first is getting the minimum necessary amount of movement, 60 minutes per day, broken up throughout the day. (Walking is enough.) The other, equally important motion is performance training — exerting yourself in an activity where you breathe heavily and exercise your heart. Do that no less than four times each week. Anyone can find the right exercise or movement routine for their life and schedule — and the benefits of training have a positive impact on not just your physical health, but your focus and mental performance.

The science behind your physical regimen

Today’s ultra athletes are better than yesterday’s. Just consider the world record for running one mile. Over the past 150 years, the fastest humans have grown 22% faster. How could this be? The consensus is that today’s athletes take the whole body system more seriously. Before the discovery of vitamins in 1912, physicians believed germs caused scurvy (they don’t, it’s due to a vitamin C deficiency) and that there were just four components to nutrition. Even into the modern era athletes didn’t prepare too seriously. To quote the 1983 winner of the Olympic marathon bronze, “All I want to do is drink beer and train like an animal.”

Athletes nowadays tend to be more circumspect and know more about how their body system functions. Which includes technologies, from what we ingest to what we wear. If you want to be an optimal athlete — whether on the field or in the boardroom — you should be thinking along multiple dimensions, too — which includes all the “STRIVE” factors in this course. They all contribute high performance.

Let’s explore the first of two types of important physical training — maintenance. The CDC recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity a week to stay well. But only 20% of Americans reach that minimum, and it’s a big part of why heart disease kills more people in the U.S. than anything else — more than cancer or car crashes, some 822,000 deaths per year. The research is emphatic: “Instant death from heart attack [is] more common in people who don’t exercise.”

Suffice it to say, your body needs a minimum amount of movement. Moving gently strains your heart, lungs, and cardiovascular system, and increases your “aerobic capacity,” or the amount of oxygen you can draw from the air during intense exercise. (The most common measure of this is VO2, pronounced “vee-oh-too.”) We need this consistent exercise because bodies index for efficiency at all costs; they economize energy and quickly atrophy away unnecessary capacity. But that can cause your capacity to fall to dangerously low levels that your biology can’t compensate for, which tips over into heart disease.

Consider 60 minutes your minimum, and spread it out over several sessions throughout the day, many sessions throughout the week. (The science goes back and forth but smaller, frequent sessions are better than infrequent, large ones.) Walking is enough. On a desk treadmill, even. (Though it’s best to “stack” benefits and get some sunlight by getting your movement or training while outside.)

Now let’s consider the other training motion — performance. This one’s more complex and encompasses all sports and anything that gets your heart racing. The more you work your heart in these conditions, the stronger it gets and the less its beats fluctuate. Lower heart rate variability means better cardiovascular function. It doesn’t hurt that some of that improved blood flow reaches your brain — people with better heart rate variability also report better mental health.

More movement also trains our bodies to better process food (metabolizing, in the parlance) and find extra hidden energy. A sedentary body isn’t very practiced at accessing stored energy — it places it and forgets it. But if you vary your training and work out at varying levels of intensity throughout the week, you help your body tap into energy stores. This produces a vibrant “metabolic infrastructure” where most of what you eat gets used.

| The three systems of your metabolic infrastructure: |

1. Alactate system — high intensity

|

2. Anaerobic system — medium intensity

|

|

3. Aerobic system — low intensity

|

Put effort into all three systems and you train your body to find, access, and use energy when you need it.

But as ultra performance athletes have learned over the last century, you can only be as effective as your vices allow. High blood sugar, inflamed lungs, high blood pressure, and habitual alcohol consumption can set you back just as much as a health kick can help. This is where your goals and the “Vision” you set for yourself can help you stay true to the goals you want to achieve.

To resist vices or other habits that may be working against your momentum, try associating yourself with “identity-based goals” not just “outcomes-based goals.” When you identify as an athlete you may start seeing yourself in a new light, making your habits and behaviors align with that new identity. As an example, people who say “I’m a runner” are better able to resist temptations and eat to fuel performance than someone who says “I run.”

We often forget that our brain is an integral part of our body, and when you care for your body you are also caring for your mental and emotional health — it’s all connected. For example, working out in the sunlight also generates vitamin D, and rapid environmental changes like cold plunges can trigger beta-endorphins which create feelings of euphoria and reduce stress-related brain activity. Exercise and physical training including mental acuity becomes a positive cycle — leaders with a physical practice are better able to calm their mind and focus at work.

Sports scientists call this the “quiet eye,” or being able to calm the mind and gaze prior to a task, in a way that increases performance. Basketball players who develop it have higher shooting percentages and can then apply that to other domains such as darts.

And here’s where all the positive effects of caring for yourself accumulate. Research shows sleep is crucial to athletics — athletes learn more and experience better muscle memory when they develop good sleep hygiene, optimizing for deep sleep and those critical REM cycles. Some research suggests shorter workdays are more productive, as are ones that follow the natural circadian rhythms of our bodies. So peeling yourself away from your desk for that physical routine — or as Exos calls them “movement snacks,” could lead to greater productivity, not less, in fewer work hours.

But how can you get more into training when you’ve been out of the habit? Consider the concept from psychology of “negative signals.” Sometimes when you stop doing the wrong thing (being sedentary) and start doing the right thing (moving), it’s unpleasant. You run and sweat and it causes your skin to itch. That’s a negative signal — it feels bad at first, but it’s actually good. It signals a breakthrough to change. As you establish a new habit that rewards you with stress relief and endorphins, your body will begin to crave and expect movement during those times of the day when you’re integrating exercise into your regular routine.

Of course, some change is harder for always-on-the-go executives to adapt to than others. Rest and recovery is a necessary part of training and movement. Taking days off for your body to recover is an essential part of the cycle of improving your physical health.

“One thing CEOs struggle with is actually realizing the importance of rest, unstructured time, and play,” says Brandon Archibald, an ultramarathon runner and executive in the construction industry. “It’s physically restorative. But it’s also a creative venture that gives the brain a non-critical task to work on while other parts of the brain are free to roam and make connections. The mammalian brain needs to burn off steam, feel alive, and recalibrate from that psychological and physical stress.”

Wisdom and interventions for training

The best routine is the one you can stick with and enjoy. After all, you are the sum of your habits. If you find joy in your routine, you’ll do more of it, and your “goals” will take care of themselves through the power of consistency.

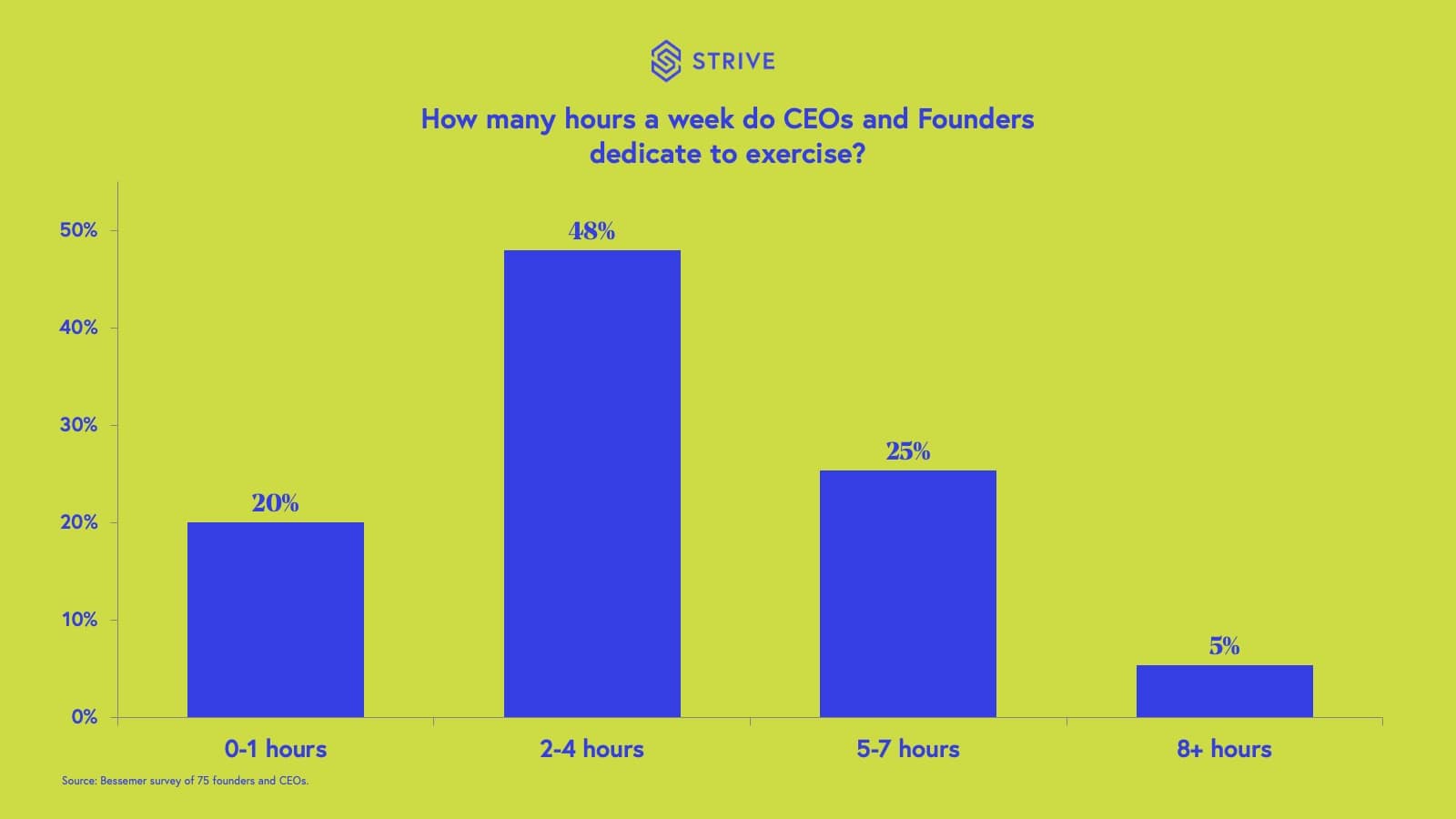

Enjoying something can help you overcome the attraction to overwork: 57% of executives tell us they are doing 60-80 hour work weeks and 54% work on weekends. And while 65% rate their physical health as “good” or “very good,” 68% say they are exercising just 0-4 hours per week. A smaller cohort are reaching the CDC’s minimum requirements for exercise. This suggests a majority of executives may have room for improvement when it comes to daily movement and training — but that’s the takeaway here: leaders can find realistic, sustainable, and consistent ways to make small improvements overtime.

Exos advises a balanced approach that commits you to both weekly maintenance and performance activities: Incorporate a variety of intensities and durations across training sessions to maintain balanced physiology.

Here’s an example training week:

| Monday | Medium intensity |

| Tuesday | Low intensity |

| Wednesday | High intensity |

| Thursday | Off day |

| Friday | High intensity |

| Saturday | Very low intensity or off day |

| Sunday | Medium intensity |

Five actions to STRIVE for improved movement and training

- Create a routine — Borrow the one above. Customize to your day and needs.

- Build a system of commitment to that routine — Find “accountability buddies” or a community that can be supportive of your habits and goals. The positive feedback from your trainer, friends, or group exercise class will help reinforce the behavior you’re looking to repeat and be a source of endorphins.

- Be mindful of your nutrition — We cover this in depth when we explore the topic of Intake, but focus your daily fueling to prepare you for your performance. For example, opt for nutrient-dense meals and snacks to help you focus at work or in the gym.

- Try technology, if that works for you — Fitness trackers can help you gain more self-awareness in your workouts while also creating a dopamine loop when you see you’ve, for example, “closed all your rings,” or achieved certain fitness goals. But only leverage technology where it helps you or solves a present problem. Many people overwhelm themselves early on with irrelevant performance data. Want to achieve a higher VO2 max? First, ask yourself what you’re looking to achieve in your training program or exercise routine. Set a goal and build habits around that first.

- When in doubt, return to your “why” — whether you’re just starting out on your exercise routine, you’re hitting new personal records, or pushing yourself to compete in an ultramarathon, reconnecting with intrinsic motivation is what helps entrepreneurs and athletes push through roadmaps and feel renewed and inspired.

If you can do all that, you’ll find that training may even become a healthy avenue for coping with stress and building a new found sense of confidence and self-esteem. All those endorphins, the increased energy, and the greater capacity to think at work pay for themselves — all while being something you enjoy enough to peel you away from your desk.