How to navigate the product-market fit journey

This framework can guide early-stage founders when striving for product-market fit, a challenging yet fundamental business goal.

“Product/market fit” is the elusive goal of every startup. It is a single business term that at once denotes successful product delivery, a working go-to-market strategy, and customer satisfaction. For this reason, venture investors seek signs of it when assessing a portfolio company or evaluating an investment opportunity. Some startups declare they have achieved product-market fit prematurely, while others don’t recognize they have it until much too late. Getting it wrong can result in a waste of resources and loss of precious time.

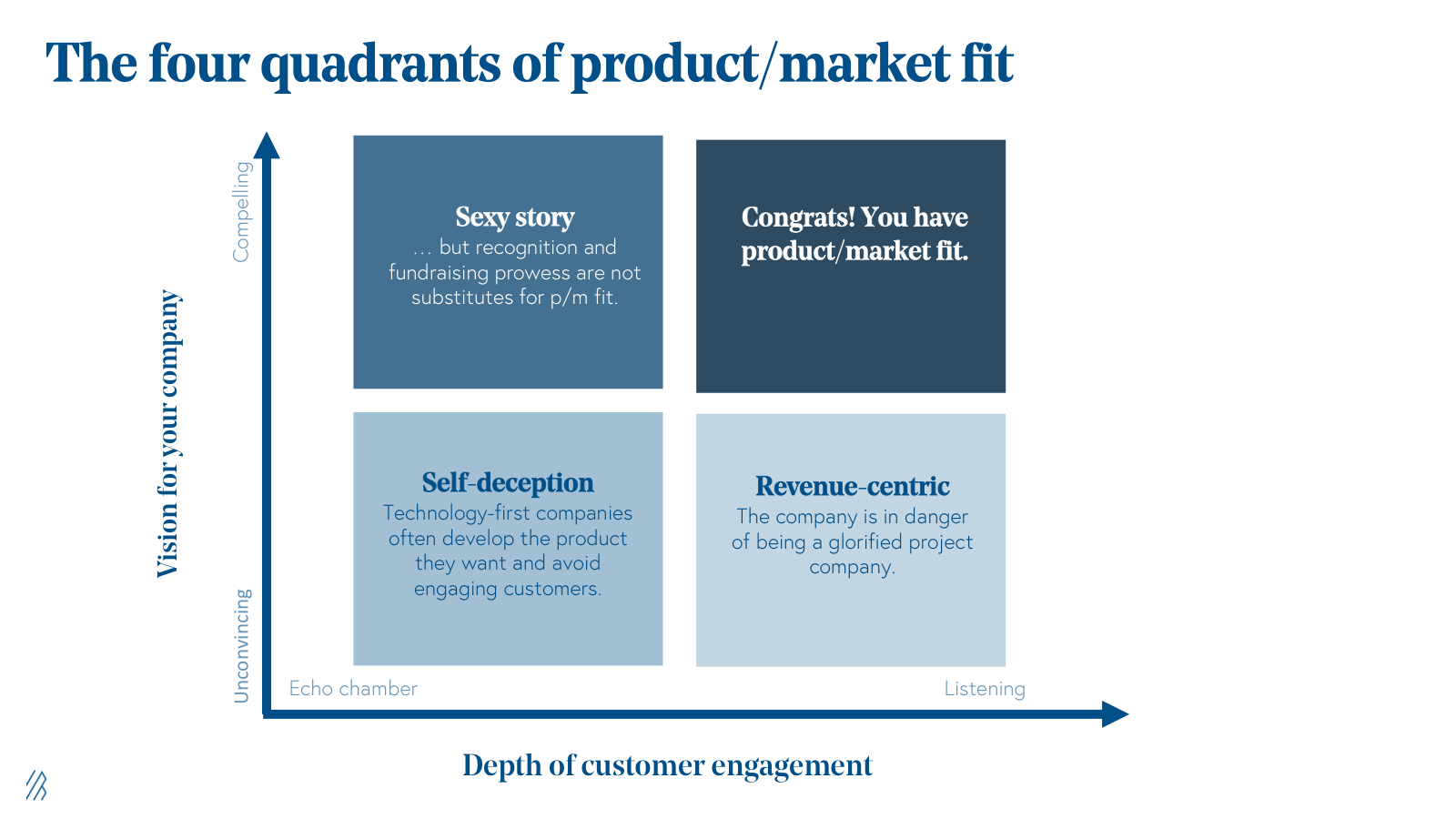

One reason it’s difficult to pinpoint is that product/market fit is not a one-dimensional continuum measured by sales growth, but rather a nuanced, two-dimensional matrix.

I developed the following diagram for founders to reflect on their own product-market fit journey, as well as for myself, to evaluate my multi-stage portfolio.

Which startup are you?

In the above diagram, the x-axis measures the depth of customer engagement, characterized by carefully listening and understanding the target customers and users. This involves understanding customer priorities, needs, alternatives, concerns, and levels of usage and engagement.

The other end of the x-axis continuum is the proverbial echo chamber. These startups are engaged with themselves and perhaps fellow startups, overconfident in their understanding of the target customer. If they are engaged with customers, they are likely preaching to the choir or else speaking to the wrong ones, those too weak and compliant to have or express their own coherent views.

The y-axis measures the strength of your product and business vision as determined by how compelling it is for prospective customers and users. A compelling product vision will be clever and innovative, with a pitch that generates a buzz among customers, partners and investors alike. A compelling vision can also be one that challenges the conventional view on a particular product or technology architecture.

The lower end of the y-axis can best be described as unconvincing, which does not necessarily imply the startup can’t sell its product. However, such startups don’t appreciate the broader strategic trends in their particular market and fail to offer the kind of vision that resonates with their audience.

It’s not enough to solely listen to customers or to rely on a compelling vision. A startup needs both, even though doing both involves tradeoffs. Some paying customers will not embrace your vision, while others will adopt your vision without conveying the insightful feedback that is so vital.

Analyzing the four quadrants

Congrats! You have product/market fit

The upper right quadrant is where everyone should be aiming, but invariably most startups find themselves in one of the three adjacent quadrants, especially in the early years. It is also natural that a startup would drift from one quadrant to another before achieving product/market fit.

Maintaining product/market fit is by no means assured in dynamic technology markets.

Of course, maintaining product/market fit is by no means assured in dynamic technology markets. Having achieved it, a successful startup may find that over time they have diluted much of their vision as they focus exclusively on hitting revenue targets, or that growing customer churn suggests they are out of touch with the evolving needs of the customer base.

Revenue-centric or sexy story

Early stage startups in both the bottom right and the top left have a degree of customer traction, but not yet enough to declare product/market fit.

Revenue-centric and sexy story startups are both susceptible to accepting a common fallacy that the early adopters of their product are also the industry trailblazers.

Not so. Sometimes your early adopters are merely your first customers. They are outliers, drawn to your vision, but there is no mainstream customer base ready to follow in their footsteps. Their eager adoption of your product may be reflective of an unsophisticated customer or just a very narrow use case. For this reason, a certain amount of time is needed to assess whether a startup’s success with its early adopters is anecdotal and fleeting, or meaningful and consistent. Getting it wrong means the startup is listening to the wrong feedback, letting it guide the product roadmap and strategy.

The revenue-centric startups that fall into the bottom right quadrant are generating sales, listening attentively to customers, and catering to their wants and demands, but to a degree, not doing so appropriately for a resource-constrained company that needs to scale quickly. In the early stages, this is a fine strategy for bootstrapping, allowing a startup to gather customer insights and learn a new domain. But startups risk getting mired in this quadrant if they lack a compelling vision or are unable to impress their vision upon their customers.

Some signs that a startup has drifted into the revenue centric quadrant include wide-ranging customer use cases, inconsistent sales cycles, product customization and a high level of post-sale service to generate value for the customer.

When any of these are combined with pricing pressure, it’s not a great sign for product-market fit. Many of the customer deals these startups close are tightly linked with adjustments to the roadmap and start to resemble “projects.” The resulting sales from such deals will keep this startup afloat, but this will mask a company that is surviving, not thriving.

The sexy story startups in the top left quadrant also don’t realize they are in this position until too late. These startups have a compelling vision and a sexy story that resonates in the media and among investors. As a result, money comes to them easily, press coverage is free and customer leads flow in. However, something is amiss, and it is typically evident in challenging unit economics, an inability to monetize a free user base, or an inability to expand beyond early adopters.

Sexy story startups conflate media and investor acceptance with customer acceptance, and don’t realize that the positive feedback they are hearing comes from an insular echo chamber.

Some sales can be bought and finagled, but are achieved at a high cost and not consistently over time. In short, these startups never really listened to their customers in the first place and found investors and media useful substitutes, assuming incorrectly that customers would eventually catch on.

Self-deception

Finally, there is the dreaded bottom left quadrant. This unconscionable location on the chart is reserved for the startup that neither offers a very compelling vision, nor listens to its intended customers. How is this even possible, you may ask?

These are typically early stage, technology companies that are convinced that technological innovation alone creates value and follow the adage, “If we build it, the customers will come.”

Obviously, it doesn’t work that way. For good reasons, these early stage startups don’t typically survive much past their Seed or Series A stages.

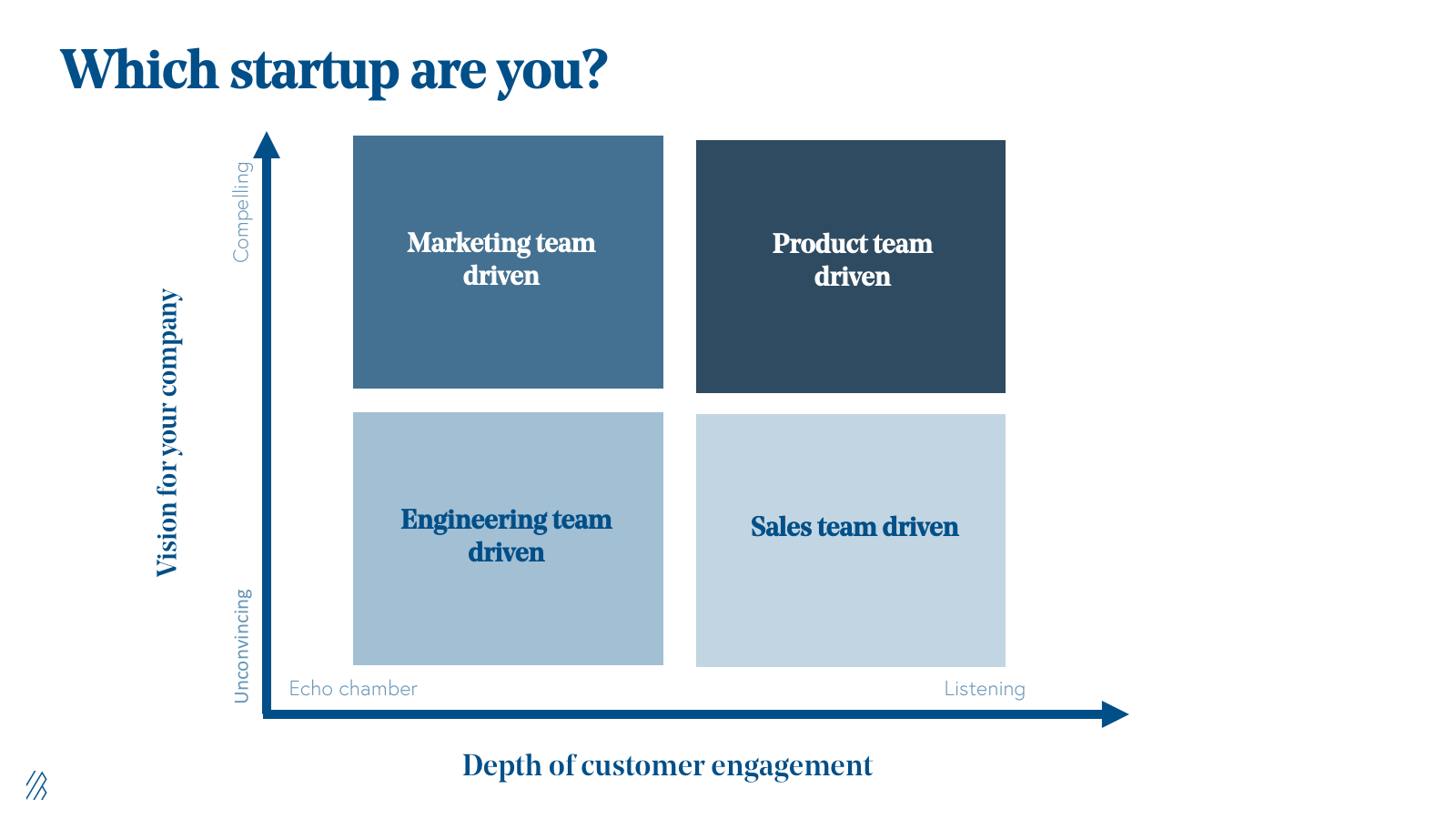

The powers that be

Another way of understanding this framework is to consider who has the greatest influence in a given startup. If the Sales organization is dominant, the startup risks falling into the bottom right. If Marketing dominates, the vision will lead at the expense of sales and true customer engagement. And if a purely Engineering mindset pervades, the startup will find itself in the bottom left.

The Product group, if sufficiently plugged into all other parts of the organization (including customers), is in the ideal position to guide the startup toward product-market fit.

Achieving and maintaining product-market fit is about balance and judgment. A startup must listen to customers, yet also guide them with a vision of their own. At times this means accepting customer feature requests that work with the product roadmap, but also rejecting those requests that weaken the vision—not simply due to resource constraints. At the same time, a compelling vision can only take a company so far and must sometimes be curtailed to focus on more immediate customer concerns and challenges.

Don’t be alarmed if you find that you are not where you want to be on this diagram. It is common for startups to feel the conflicting forces that pull the company in seemingly contradictory directions. As long as you are conscious of the dangers of compromising on either of these two measurements of product-market fit, you are less likely to remain stuck in the wrong quadrant.