The Five Waves of Fintech

To know the future of fintech you must first know the past. We reflect on how changes in technology, regulation, customer expectations, and macroeconomics transformed financial services over the last few decades.

The financial services industry is as old as money itself. Its history of innovation weaves through the rise and fall of societies from the Roman Empire to the House of the Medicis, the Morgans, and beyond. However, for most of the 20th century, innovation was largely driven by the invention of new products. For example, mortgage-backed security (MBS) was an innovation that emerged in the 1970s when Ginnie Mae (the Government National Mortgage Association) allowed banks to free up liquidity and sell their mortgages to third-parties, who packaged them into MBS. Fast forward to the downfalls of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature, and Silvergate, regulation and macroeconomics still have profound impact on the fintech ecosystem.

Aside from new products, re-packaging of risk has also long been a form of reinvention in financial services. But it wasn't until the rise of the internet that technology allowed innovators to prioritize the customer's needs and create new products and services that were friendlier and more accessible. For example, in 1998, Paypal was one of the first "consumer earthquakes" to digitize peer-to-peer payments, leading to monumental changes: Money could be transferred via the internet? A revolution. But that wasn't all. The aftershocks of innovation continued throughout the early 2000s, inspiring a new generation of fintech entrepreneurs.

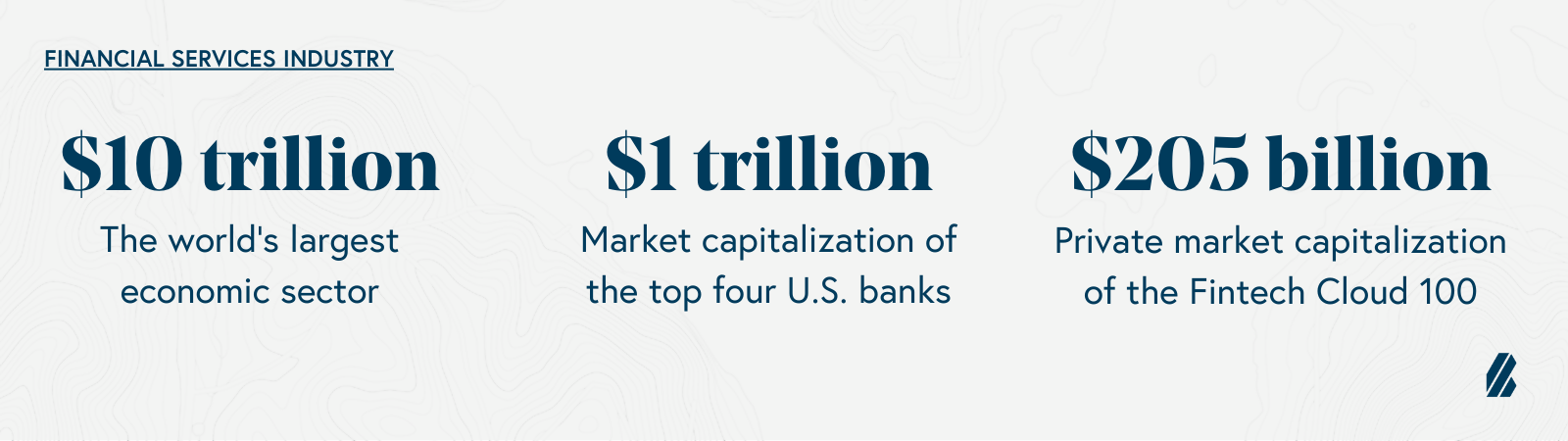

Take Matan Bar, former product leader at Paypal. After his time at one of the original fintech juggernauts, it was clear to him that there was a massive gap in the payments market—while consumers had P2P (peer-to-peer) solutions, small businesses struggled to make vendor payments seamless. Matan and his co-founders built Melio, one of the first platforms to make B2B payments easy. Finally, small businesses could wield that same magical, “consumer-like” experience with just a few clicks. Melio’s origin story is just one example of the thousands of fintech builders who have pushed the industry forward in a short time. And arguably, the financial services industry still holds the most opportunity for disruption since it is the world’s largest economic sector.

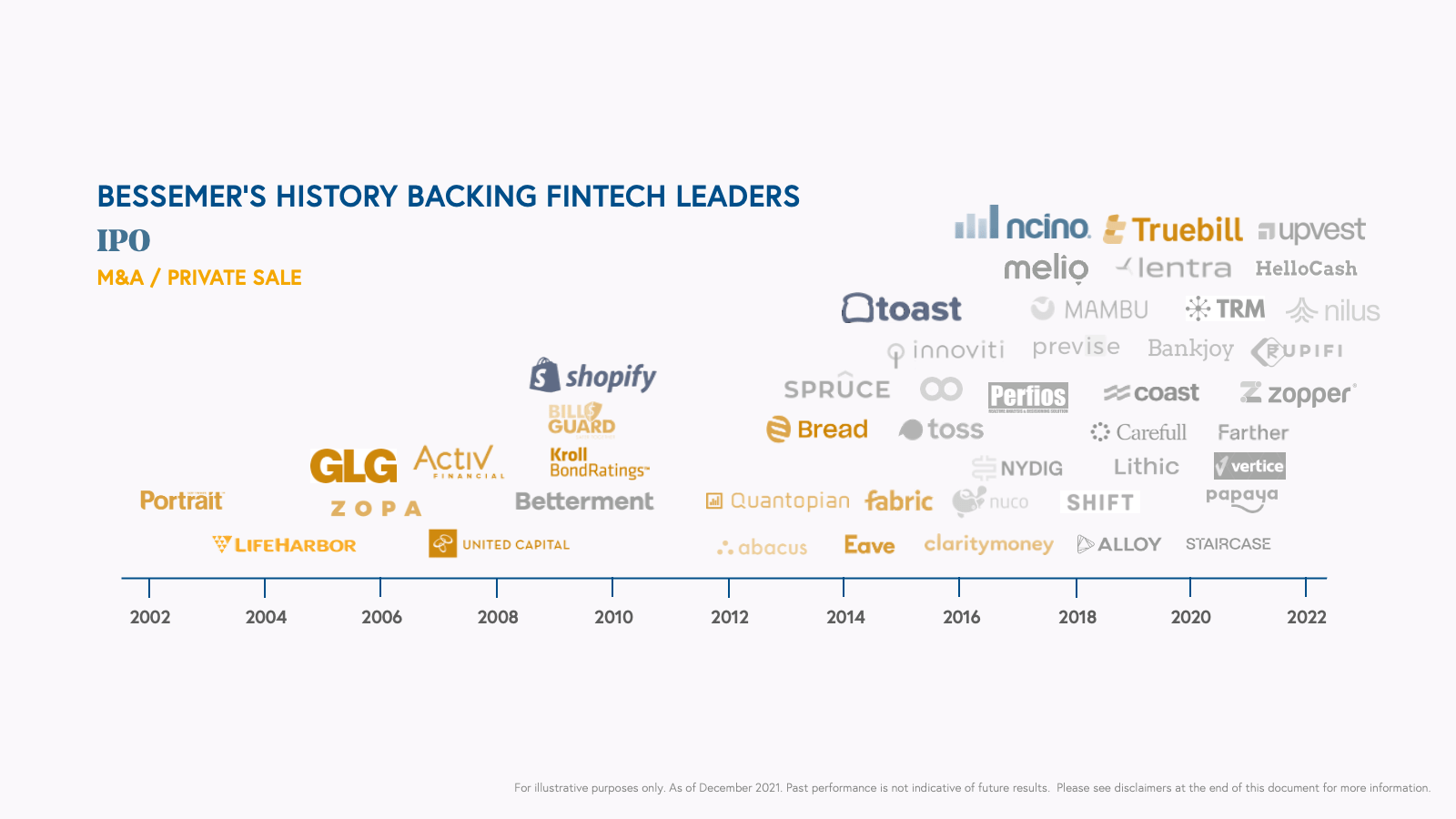

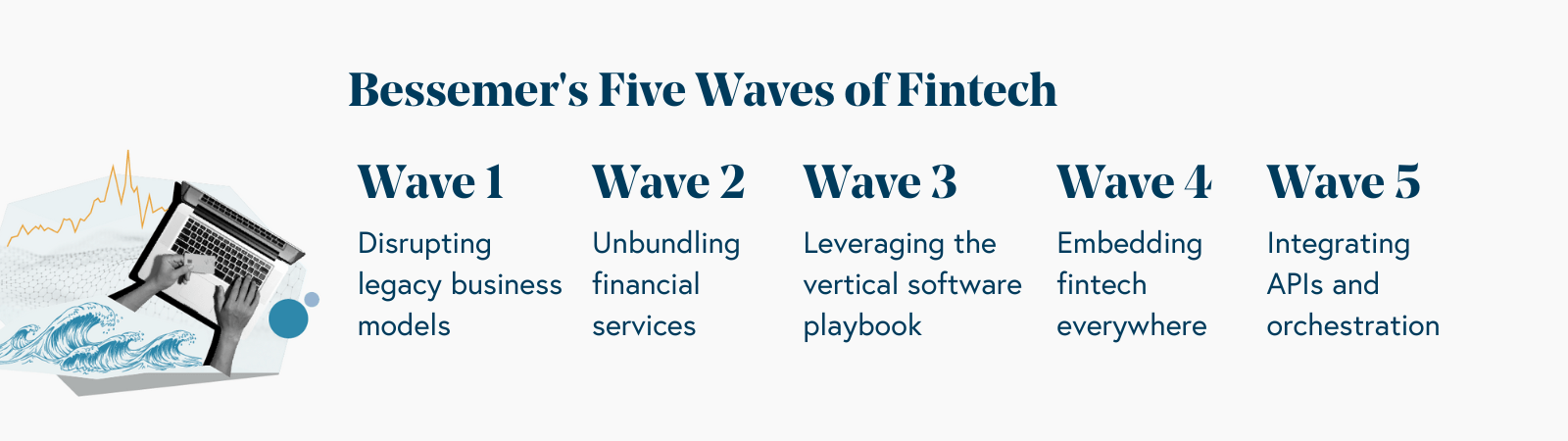

Over the past few decades, Bessemer’s investment strategy has tracked the major shifts in mobile adoption and the cloud, along with regulation and macroeconomics, and will continue to be driven by these changes in the future. Since our early days of investing in the sector, we have identified five massive waves that drove over 50 investments supporting and disrupting financial services—including companies like Alloy, Mambu, and Truebill, which transformed consumer, enterprise, and embedded fintech. Each of these five waves contains powerful lessons that, if studied carefully, will help today’s builders more easily spot the next swells of opportunity ahead.

Wave 1: Disrupting legacy business models

Technological advances always spur entrepreneurship, but in the financial services industry, a disproportionate number of businesses start in response to macroeconomic and regulatory shifts. As fintech investors, we’ve seen that innovation can happen at the business model level even without groundbreaking new technology.

For example, after the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, investors grew skeptical of the traditional equity research model. Firms gave clients reports and recommendations by often promoting investment banking clients to the detriment of their research clients. In this model, buyers suffered from a limiting dynamic: the value of investment information decreased as more investors had access to the same information. However, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG) offered an alternative model—a marketplace for information that would ultimately benefit from network effects.

Unlike other equity research providers, GLG connected clients with carefully screened experts, giving them access to information no other client had. GLG did not devalue its services like other equity research providers and avoided conflicts of interest.

We saw another example of business model reinvention when The Great Recession in 2008 exposed other vulnerabilities in existing business models. Consumer confidence in the major brokerage houses was in decline when we invested in United Capital in 2009. We believed that the independent Registered Investment Advisors' assets under management (AUM) model better-aligned advisor and consumer incentives and that consumers would shift wallet share away from wirehouses. (Wirehouses' commission revenue incentivized fees from more trades and the marketing of in-house products.) The United Capital platform leveraged centralized technology and operations to deliver this vision with an incentive structure that was a win-win for the advisor and client.

Today, business model reinvention in financial services continues to unfold. Take the simple example of the credit card: we now see credit cards secured by automobiles, home equity, crypto, and equity investments that can offer consumers a lower annual percentage rate (APR). Other upstarts are innovating on longstanding financial products such as employee stock ownership plans (ESOP), pre-tax benefits, and property ownership for both businesses and consumers. In short, innovation in financial services takes many different forms, and we are eager to support disruptive technologies and business models.

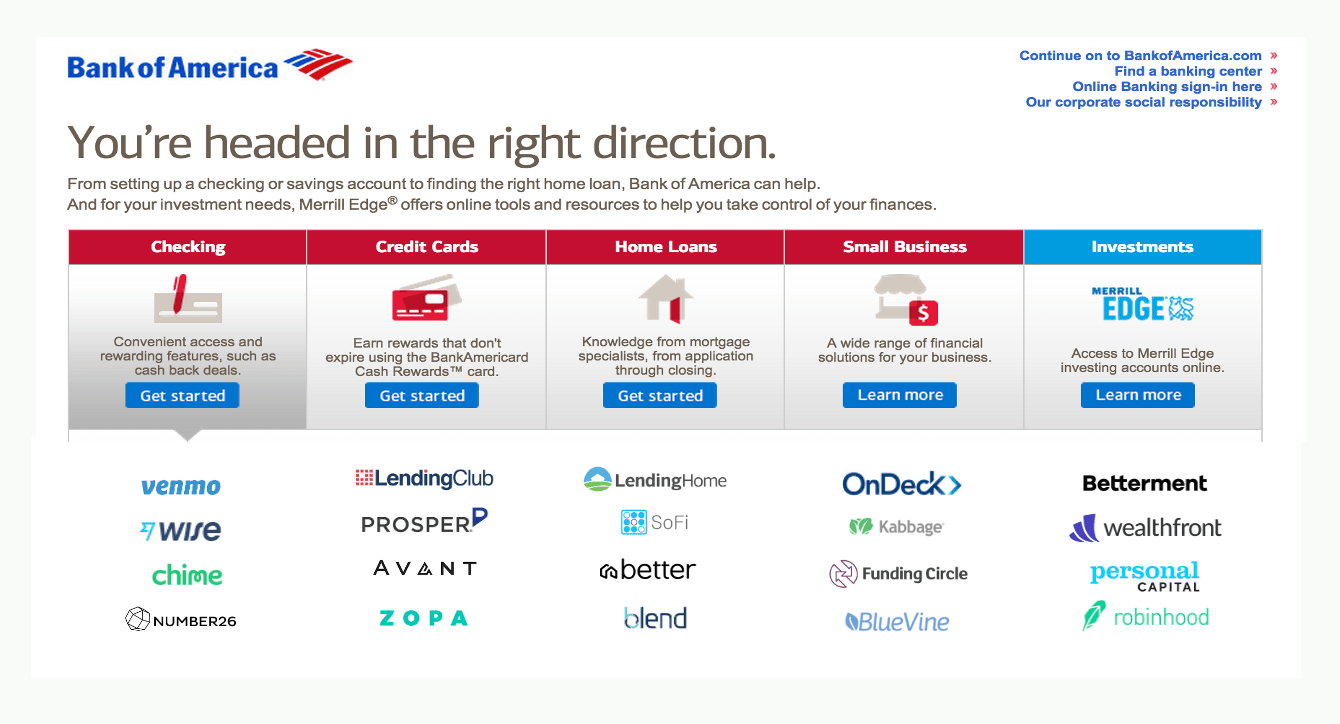

Wave 2: Unbundling financial services

Many argue that “the great unbundling” of financial services that began in the early 2000s was the dawn of the fintech era. Fintech entrepreneurs sought to find a product wedge and create a structurally cheaper operating model that lacked the overhead, physical networks, and often capital and regulatory requirements of traditional financial institutions. The result? Far more “user-centric” products for customers that could be accessed via the web and mobile apps. These products were more in line with the seamless technology that customers were becoming used to outside of financial services.

The unbundling of wealth management, a once gated financial service, was driven by the belief that wealth management should reach a broader audience with a straight-forward, affordable, and more accessible product. In 2010, we invested in Betterment. Its seamless and more accessible onboarding flow paired customers with low-cost ETFs and a portfolio of U.S. treasuries, according to their risk tolerance. At the time, web-based platforms for retail investors catered to sophisticated investors with complex products.

Betterment, meanwhile, catered to everyday people. The onboarding simply asked three questions to determine risk tolerance. Betterment’s product experience was so simple that it unlocked word-of-mouth promotion from its users, leading to an effective early distribution mechanism until the brand and product became established in the market.

The “free lunch” is an effective acquisition strategy in fintech.

However, the most effective customer acquisition strategy in consumer fintech has arguably been the “free lunch” strategy. Free lunches are features or aspects of the product that feel free to the customer, but actually generate revenue for the fintech provider and give the business an initial wedge to set up future, additional monetization streams.

Even before the consumer fintech wave of the past two decades, traditional banks have long been using free checking as the classic consumer hook. At most banks, it’s free to spin up a checking account and deposit money. However, the bank then lends that money out, earning revenue through interest, which in turn is used to service the costs to manage the deposits. More recent examples of a free lunch hook are no-fee trading products like Robinhood, which generates revenue primarily from payment for order flow.

Many innovators across our portfolio have leveraged a key acquisition or distribution hook: Toss gained viral adoption by offering free peer-to-peer (P2P) payments in South Korea and then rebundled to offer additional services such as budgeting, lending, and investing products. Truebill dazzled customers with a magical product experience saving users money on their subscriptions. Papaya Payments attracted droves of users by paying their bills with just a picture — a “free lunch” for users enabled initially by interchange revenue where merchants were already accepting those fees.

Today we see startups focusing on targeted demographics (such as Gen Z, the elderly, and creators) and using distribution hooks that drive long-tail monetization (such as via landlords, credit bureaus, and tax software). This more recent wave of consumer fintech innovators has also been enabled by the proliferation of modern fintech infrastructure providers that did not exist in the 2000s and early 2010s (like Plaid, Alloy, and Lithic), empowering entrepreneurs to bring products to market quicker and cheaper.

Wave 3: Leveraging the vertical SaaS playbook

Over the past decade, our investments in companies like Shopify, Procore, and Toast illustrated how vertical software companies were like “sleeping giants” that smashed many people’s expectations for growth. Cloud-based technology with tailored workflows and feature sets proved to unseat incumbents or create new software markets.

Many vertical SaaS principles apply to financial services, but the most successful challengers rarely go to market with a “rip and replace” strategy. Building a more focused product can be a “Trojan Horse strategy” to land large customers and expand with new products and services over time, often alongside the incumbents.

In the case of nCino, the founders recognized that the incumbents were not focused on providing modern software for the origination of commercial loans, especially for community banks and credit unions. nCino had the opportunity to deliver beyond its initial CRM offering and build a “layer cake” of products and services. Soon they grew customer relationships significantly, often becoming their clients’ system of record by building precise workflows for underwriting and document collection.

A similar dynamic existed in the insurance market, where carriers were well-served by large, legacy core software providers like Guidewire, Vertafore, and Applied Systems. However, there was a significant gap in insurance creating an opportunity for intelligent fraud detection using more modern machine learning principles. Shift Technology built an AI-based solution to address this need initially. Over time, they have moved into end-to-end claim automation and underwriting fraud detection. This product expansion strategy focused on processing workflows and efficiency—a page pulled from the playbook of best-in-class vertical software players.

As Shopify did with emerging e-commerce providers in their earliest days, core bank software innovator, Mambu, rode the consumer fintech wave by serving emerging challenger banks and non-bank lenders with early customers like N26 and OakNorth. However, to gain massive scale, Mambu always planned to also move into the market of more established players to disrupt the industry.

As investors, we encourage future fintech founders to take advantage of the incumbents’ strengths when possible, but innovate by attacking their weaknesses. Many of the most successful fintechs have been built on top of Visa or Mastercard’s networks, the banking cores’ distribution, or in partnership with the largest banks’ balance sheets, while slowly chipping away at other incumbents’ market share.

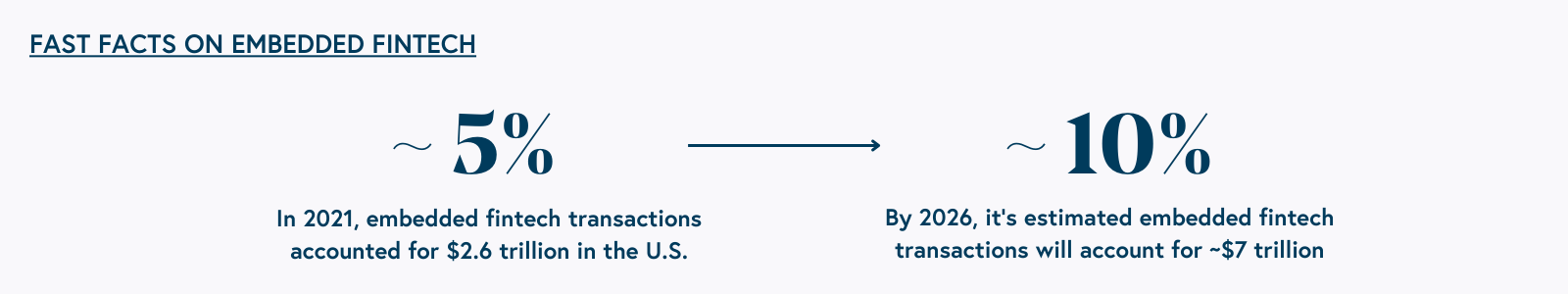

Wave 4: Embedding fintech everywhere

Most of our vertical SaaS leaders emerged as market-defining companies through the power of “The Second Act.” In many cases, these businesses leveraged new payment products and embedded fintech solutions to expand their addressable markets, drive product stickiness, and expand their average contract values. In 2022, for example, Shopify and Toast were generating over half of their revenue from payments. (Shopify issued $1.7 billion in merchant cash advances in 2022.)

Giants like Walmart, Uber, Apple, Google and the airlines have all continued to double down on financial services, spanning banking, payments, payroll, and insurance offerings. Their massive distribution advantage provides an opportunity to expand margin and customer value through financial services and provide customers with a better and more contextual purchasing experience.

Previously, we’ve seen embedded fintech products as accelerators to market leadership after SaaS businesses launch their initial product offering. However, today, many application software providers are beginning with fintech monetization as their initial business model and using inexpensive software that solves industry specific problems as their go-to-market strategy..

Thanks to the proliferation of APIs, it is easier and more cost effective than ever to build products that monetize indirectly on a range of ancillary services. Every slice of the fintech stack can be abstracted away to an infrastructure provider who could expedite speed to market and handle the complexity of financial services.

Plaid was one of the earliest examples of this for bank connectivity. They were soon one of many infrastructure providers whose functionality spawned an entirely new category of businesses while also serving incumbents. Lithic (formerly Privacy) was also part of this rising tide of embedded infrastructure with their developer-first card issuing API. Through Privacy, founder Bo Jiang saw the need for a modular and flexible solution firsthand. What would take an incumbent three to six months with their sales and integration process, Lithic could stand up in 24 hours.

But card issuing is just one slice of infrastructure making financial services accessible for any business. We stayed laser-focused on the companies that best exemplified our developer laws, a set of principles we distilled from observing the most successful developer companies.

Best-in-class companies had frictionless products that solved complex problems and were evangelized by developer communities, but were non-core in terms of development.

For financial services developer platforms in particular, this complexity takes on additional meaning—regulatory complexity, technical complexity, and counterparty risk. To successfully handle this, we encourage founders to go deep and solve fewer problems well, rather than going wide. Breadth without depth often leads to customer churn as they are unable to scale with basic solutions that are unfit for more complex and mature businesses.

Wave 5: Re-bundling financial services with an “API for everything” and new orchestration layers

After a decade of unbundling of financial services to better serve each customer’s vertical needs, a renewed focus on sustainable economics pushed a re-bundling. Companies like LendingClub, SoFi, Zopa, and Revolut expanded far beyond their initial offerings and, in some cases, secured banking licenses to become full-stack financial institutions taking in their own customer deposits.

To service the re-bundling, entrepreneurs have built an API for everything and orchestration layers that sit between end points so that re-bundlers could provide a platform where its value was greater than the sum of its parts.

The need for these orchestration layers led to our investment in Alloy—which we believed would be a key enabler of the growth in online account opening and fintech innovation more generally. Identity management is fragmented across a myriad of providers and, while it’s mission critical, it shouldn’t always require in-house development to be best in class. The single connection to the Alloy API enabled financial institutions to work with their customers’ existing identity and fraud-related data providers while adding new data offerings to become the true identity management operating system.

There are still many corners of financial services that would benefit from an orchestration layer that abstracts away the pains of integration and unlocks incremental value in the data through aggregation. Orchestration is a way to improve the efficiency and efficacy of developer teams by enabling them to focus on the core competency of the business. For example, we strongly believe that large swaths of product and engineering teams should not be dedicated to building integrations to the hundreds of payroll and HRIS data sources, commerce data sources, or accounting and financial data sources. These platforms can enable entirely new businesses to exist that would have previously required disproportionate engineering effort.

What swells are we excited about?

The decade ahead will inevitably bring regulatory and macroeconomic changes along with shifting customer expectations. We foresee emerging entrepreneurial opportunities in five key areas.

- Faster payments. Businesses everywhere will begin to adopt faster payments given increasing working capital needs paired with the launch of FedNow and other government backed initiatives. The rise of real-time payments and settlements will significantly impact supply chains, financial institutions, and consumers. We expect infrastructure providers to help institutions connect, manage workflow, and address fraud—especially authorized push payments.

- Fraud prevention. New modes of fraud will continue to emerge and evolve rapidly as money movement changes, driving the importance of businesses sitting at the intersection of financial services and data privacy and security. For example, after the SVB closure, reports of B2B wire fraud skyrocketed.

- Intersection of fintech and healthcare. As the financial services and healthcare industries both finally move into the cloud era, entrepreneurs will innovate at the intersection of the two largest sectors in our economy to solve some of the most pressing issues in the U.S. financial system caused by rising demand for healthcare. This includes areas such as healthcare revenue cycle management, claim payouts and acceptance, and financial products focused on an aging population.

- Institutional Blockchain. Despite “the crypto winter,” we’re excited to see large institutions adopt blockchain technology to solve real problems in both consumer and commercial banking, including examples such as USDF Consortium, SWIFT’s central bank digital currency (CBDC), and JP Morgan’s private blockchain (Onyx.)

- Generative AI. Since 2023 is the year for generative AI, large language models will transform how fintechs interact, communicate, and provide intelligent insights for their customers at scale and businesses across the financial services landscape will look to leverage these new technologies. While financial services pose a unique challenge in that much of the data is private and does not live across the public internet, we expect to see vertically specific fintech “Copilots” enriched with internal data and traceability.

While we anticipate changes in these five areas, we also know that in any field of innovation, the coming years will also present unforeseen challenges and opportunities. We know builders will meet these challenges head on—and we’ll be there to support them every step of the way.

Are you building in a current or emerging wave of fintech? We want to hear from you. Reach out on Twitter—Charles Birnbaum (@cbirn) and Eric Kaplan (@eric_kaplan_nyc).