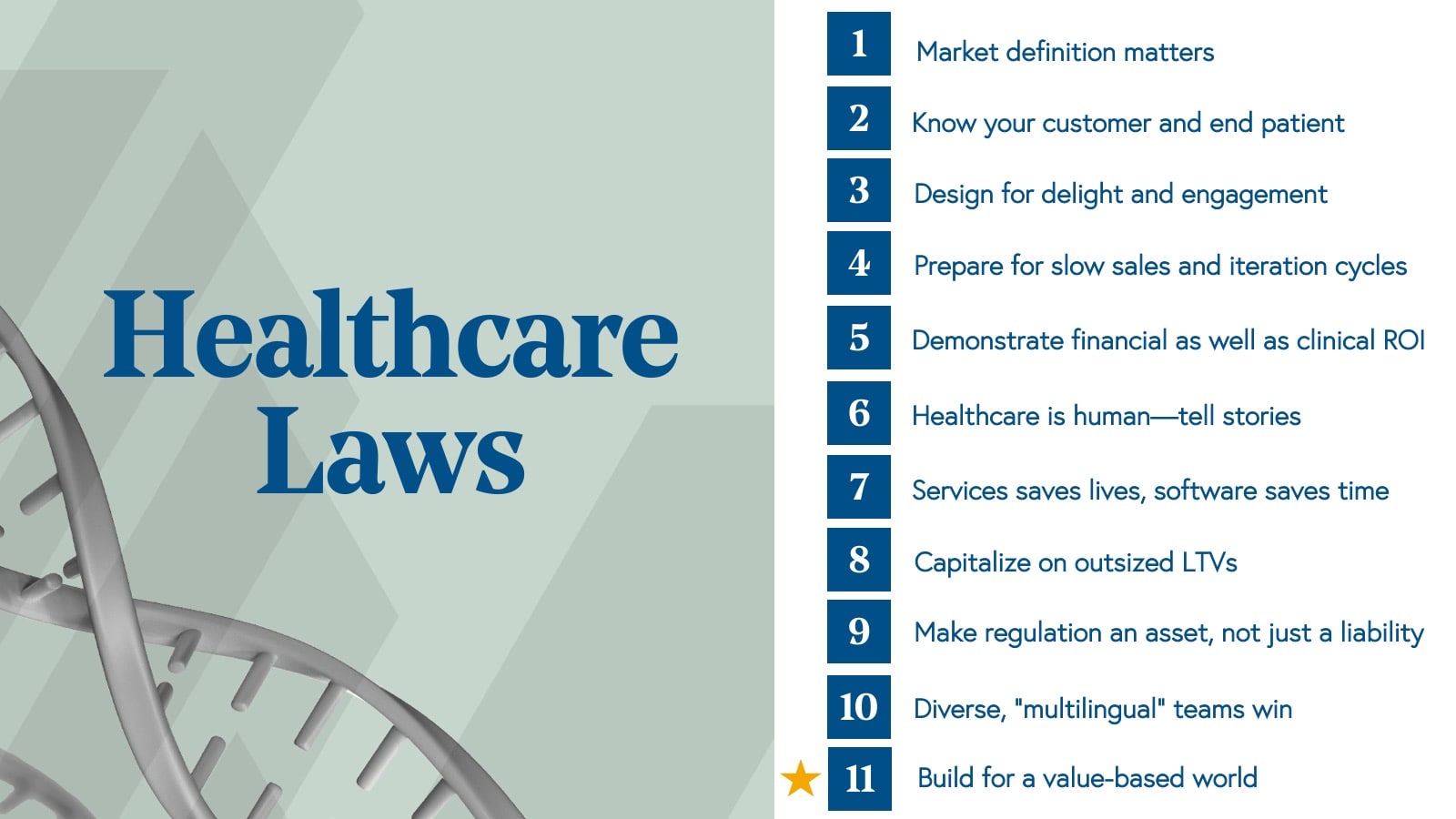

Roadmap: 10 Laws of Healthcare

After four decades of investing in the industry, Bessemer offers the guiding principles for healthcare founders, executives, providers, payers, employers and patients who are building tomorrow's innovations and systems of care.

Cloud computing completely changed the trajectory of consumer and enterprise software. Similarly, the digitization of healthcare data over the last decade has created a massive opportunity to redefine care delivery, accelerate pharmaceutical innovation, and reinvent how patients interface with the system and engage with their care.

“Today, healthcare providers rely on connected EMRs, though that’s a bit like having internet access but only being able to read news stories based on bits and pieces of facts that are weeks or months old,” said Chris Klomp, CEO of Collective Medical. “In the future, most healthcare decisions will be based on collectively-derived insights that are synthesized in real-time and delivered at the point of care.”

As a result of the digitization and increasing liquidity of healthcare data, today, we’re seeing record amounts of innovation and investment in the industry from a variety of participants, such as startups and large tech companies, as well as big-box retailers and traditional healthcare organizations.

We hope that Bessemer’s 10 Laws of Healthcare will shape future decisions as leaders and providers build new systems, innovations, and services in today’s increasingly complex healthcare marketplace.

But given that we’re launching these healthcare tenets amidst the Corona virus, it would be remiss of us not to mention the serious impact COVID-19 has had on our system, country, and the health of the global community. In these uncertain times of a worldwide pandemic, we celebrate those in healthcare, technology, and manufacturing who are tackling the most pressing issues facing our healthcare system today. (In fact, A Healthy Dose podcast launched a mini-series where Steve Kraus and Trevor Price talk to experts and leaders of the COVID-19 crisis.)

We are grateful for the relentless effort of our frontline healthcare providers and staff who are risking their lives during this time. As part of our recovery from this crisis, we expect significant reform in the U.S. healthcare system, which will include expanding telemedicine geographically and technologically, furthering the development of remote monitoring technologies for use in routine clinical care as well as clinical trials, and transforming the system’s supply chain.

Law 1: Market definition matters

Healthcare represents approximately 18% of US GDP or, in other terms, $3.6 trillion of annual spending, and continues to grow by low, single-digit percentages each year. Despite the impressive scale of the US healthcare industry, not a single healthcare company has a $3.6T total addressable market (TAM).

Instead, healthcare looks a lot more like several thousand billion-dollar markets that include everything from healthcare technology, commercial and government-sponsored care to drugs, medical equipment, home health services, out of pocket costs, and more, all of which together comprise the $3.6T industry figure.

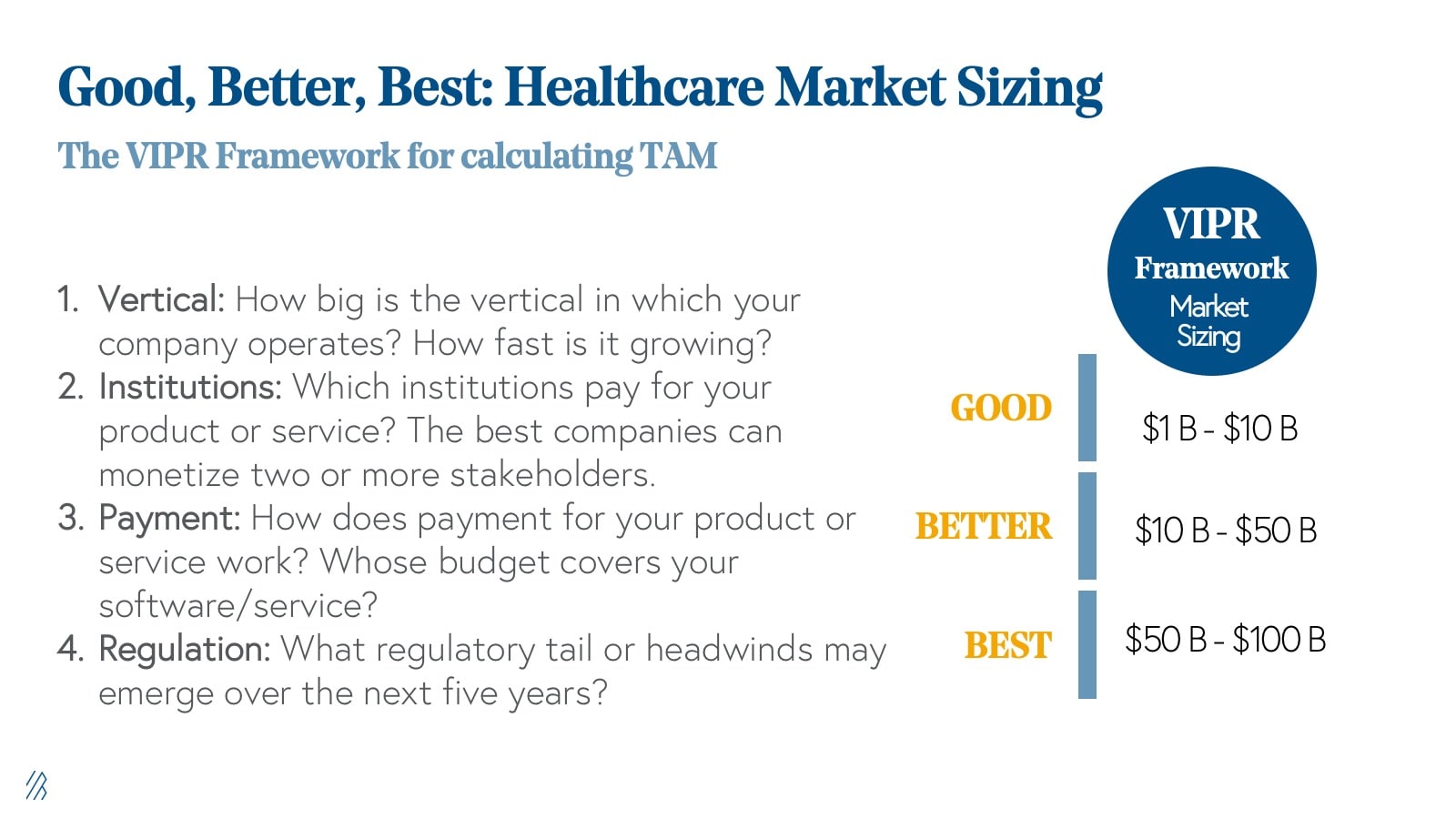

In healthcare, when investors ask a company to define the total addressable market (TAM), we think it’s essential for teams to anchor on more realistic, bottoms-up analyses that account for the per unit/service revenue (or margin) and the total number of buyers or addressable/attributable patients.

A robust understanding of your company’s immediate TAM is critical for seeking outside investment, developing your go-to-market strategy, and ultimately deciding what your company looks like when it’s all grown up.

Still, even when leveraging a bottom-up approach, we often see healthcare companies over-estimating their addressable market size. To hone in on a more accurate TAM, one that a founder and their investors can believe in, we recommend the VIPR Framework.

The VIPR Framework for calculating the Total Addressable Market for Healthcare Companies

1. Vertical: How big is the vertical in which you operate? How fast is it growing? At Bessemer, we often think of TAM in two ways: (1) Immediate TAM, or the TAM for the current product/service as offered, and (2) “Big Hairy TAM,” or the TAM that your company could address with additional product and/or customer expansion. Healthcare companies should have a pulse on both.

2. Institutions: Which institutions pay for your product or service? Providers? Payers? Employers? Pharma? Patients? We often see that the best companies can monetize two or more stakeholders.

3. Payment: How does payment for your product or service work? Whose budget covers your software/service? Do you process claims, charge for SaaS licenses, charge via cash pay, receive value-based payment, or some combination of these four? How does your payment mechanism impact your cash flow?

4. Regulation: What regulations govern your product or service today, and what regulatory tail or headwinds may emerge over the next five years? Do these regulations affect reimbursement for your product or service? And if so, what markets become unlocked?

As an example, let’s look at the VIPR framework for Livongo.

Livongo is a healthcare technology company that helps people with chronic conditions and is one of the earliest leaders of the digital health sector. One of the populations Livongo serves is people with Type 1 diabetes, also known as insulin-dependent diabetes, which we will focus on for this analysis.

Vertical: The immediate TAM is composed of self-funded insurers, which is defined as the number of members covered by self-funded employers, multiplied by the prevalence of insulin-dependent diabetes, multiplied by the per member per month fee (PMPM fee). This approach would have worked best for Livongo’s early days before they had data on what percent of insulin-dependent diabetes patients they could capture at self-funded employers (penetration rate).

(# of members covered by self-funded employers) x (prevalence of insulin-dependent diabetes) x (PMPM fee) = Immediate TAM

Another way to calculate this immediate TAM is to take the number of members covered by self-funded employers and multiply that number by Livongo’s historical penetration rate multiplied by the PMPM fee. This approach will yield a more precise TAM estimate for Livongo because there is sufficient data to validate that the historical penetration rate is repeatable.

(# of members covered by self-funded employers) x (Livongo historical penetration rate) x (PMPM fee) = Immediate TAM

Then there’s what we call the “Big Hairy” TAM, which includes commercial and government payers, pre-diabetes patients, and probably other chronic conditions related to behavioral.

For example, to find the Big Hairy TAM, take the number of members covered by self-funded and fully-insured employers, Medicare, and Medicaid multiplied by the prevalence of insulin-dependent diabetes, and other chronic conditions such as behavioral health multiplied by the PMPM fee.

(# of members covered by self-funded and fully-insured employers, Medicare, and Medicaid) x (prevalence of insulin-dependent diabetes, prediabetes, behavioral health, etc.) x PMPM fee

OR

(# of members covered by self-funded and fully-insured employers, Medicare, and Medicaid) x (Livongo historical penetrate rate for insulin-dependent diabetes + projected uplift for additional chronic conditions) x PMPM fee

Institutions: Livongo initially sold to self-funded employers, and over time, has expanded to both commercial and government payers.

Payment: Patients are billed through claims or via invoice based on per member per month pricing. Payment depends on the sophistication of revenue cycle management function for claims processing and payment terms with customers.

Regulation: An example of a regulation that could catalyze customer growth and sales for Livongo is the new CMS rule for remote patient monitoring (RPM) reimbursement. The rule creates current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (used for billing) that enable Medicare reimbursement for RPM services. This rule could unlock opportunities with hospitals and health systems, which now have an additional financial incentive for using Livongo.

Law 2: Know and engage with your customer, and ultimately the end patient.

Today, buyers of healthcare solutions want to pay for engagement. Tomorrow, these decision-makers, such as CXOs at healthcare systems and HR executives at employers, will pay for value, and engagement will be table stakes. The first step toward delivering value, the holy grail of all healthcare companies, is to have patients engage. To increase engagement, companies must demonstrate that their products and services drive improved clinical outcomes and cost savings over time.

Early-stage tech-enabled healthcare companies might lack sufficient, actuarial grade data to make claims about the clinical and financial impact of their products or services. Lacking the robust evidence of improved outcomes can occur even when the traditional care delivery paradigms, which are not tech-enabled, are rooted in clinical evidence (e.g. digital cognitive behavioral therapy, also known as CBT, vs. traditional).

The best way to acquire and test this data is to collect it from patients and healthcare institutions as they interact with your company. However, the line between wellness and evidence-based interventions is more blurry for consumer-facing applications than it is for those that sell to health systems, payers, and employers. As more digital companies pivot to a B2B2C model, your company can expect to face increased scrutiny, or the “wellness until proven otherwise” conundrum. In this circumstance, employee satisfaction and engagement become primary company metrics before outcomes and cost savings.

Most digital health products work to change patient behavior and promise actionable insights as a result of the company’s collection of patient data over time. However, as it stands today, quality data exhaust is hard to come by as almost two-third of digital health apps support fewer than 1,000 MAUs. These uninspiring statistics are not a reflection of the market potential, but rather how difficult it is to acquire patient-users in a scalable fashion and deliver on a sustained health or wellness value proposition. Without robust patient engagement, your product is at high risk for churn and becoming another forgotten-about silo in the healthcare stack.

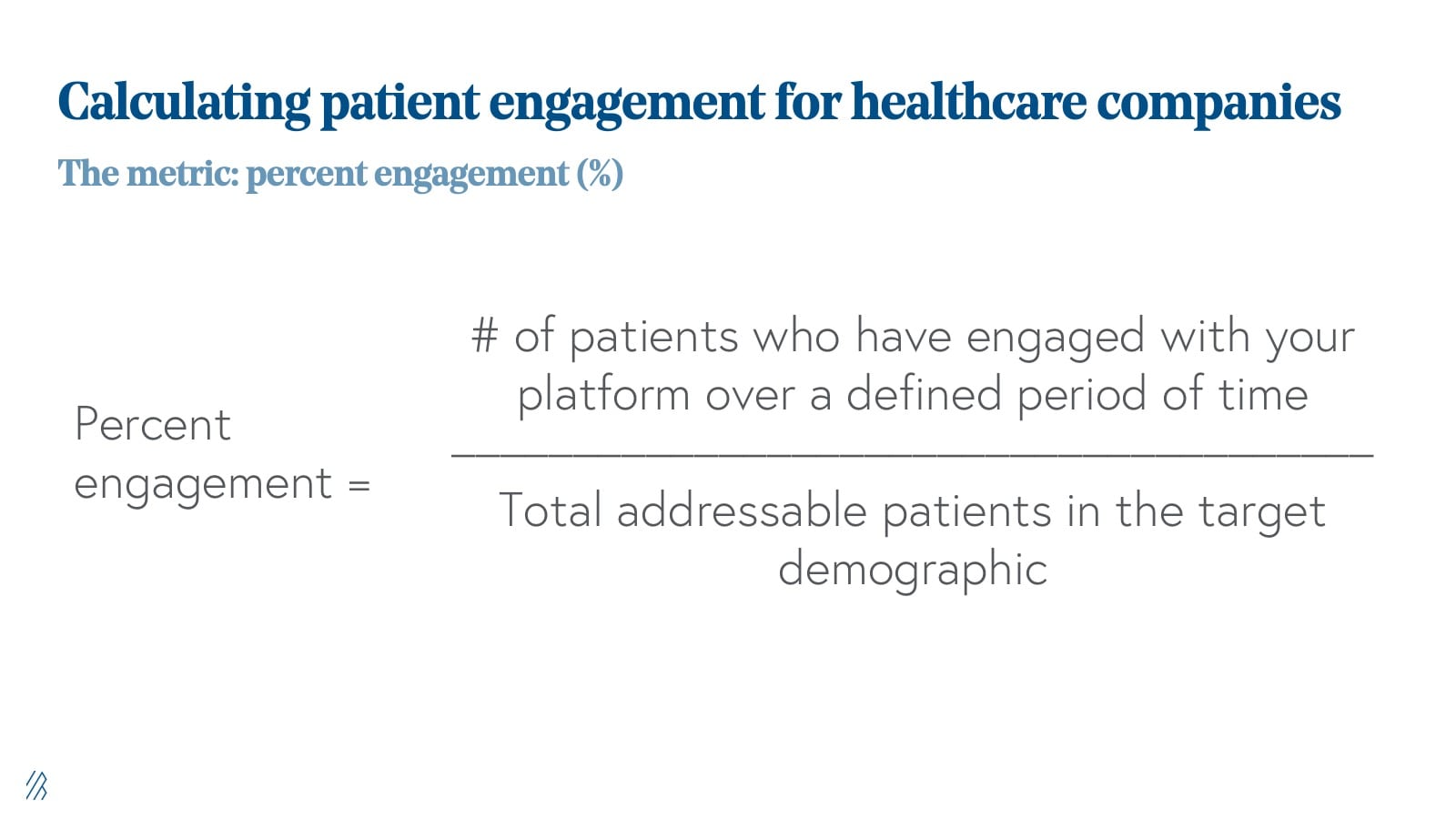

So how do you improve engagement to drive desired outcomes? A compelling engagement narrative is only as good as the framework used to benchmark it. We see the best companies do the following:

- Articulate what engagement means for their platform clearly. For example, the number of logins may not be the appropriate metric if your platform asks the end-user to act to generate a certain desired result.

- Identify the right patient at the right time using specific parameters. Does your end-user have a particular role in the back office, or do they have a specific diagnosis or claim filed over the last year? Are you targeting chronic or acute patients?

- Why does this stakeholder (patient, provider, executive, etc.) need your solution now? What is their current workflow? Does your product or service interrupt, support, redesign, or integrate with the current workflow? Are there material switching costs associated with trying our solution?

Engagement strategies vary wildly across end-users, whether you are selling to a healthcare worker, executive, or patient, and across patient populations and disease states. While you want to expand your total addressable market over time, an early-stage company can start with a much more narrow market as long as there is deep engagement with your core audience. For healthcare companies, it’s not just about how many people you engage, but it’s also whom you engage with and at what stage of the customer or patient journey.

Careful consideration of who your patients are, empathy for their daily experiences, and an understanding of whether they are the right patients for your product or service will go a long way in terms of improving upon your product or service’s engagement metrics.

For example, Hinge Health is a coach-led, digital therapy platform for self-insured employers and health plans that provide care for more than 124 million U.S. adults living with musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders. In order to improve the health outcomes of this patient population, Hinge Health focuses most on serving people living with chronic MSK disorders as these patients have the highest risk and are the highest cost members. Focusing on this cohort of patients is an engagement strategy that serves people with the most need while also driving down the employer’s bottom line. Ultimately, digital therapy platforms like Hinge Health provide access to care at a lower cost, reducing the occurrence of unnecessary surgeries and spending on opioids.

According to Daniel Perez, co-founder and CEO of Hinge Health, driving engagement can go a long way for patient populations: “When a patient has a relationship with a real person on a care team, it boosts their adherence to the care plan. Critically that person doesn’t have to be a doctor or even a nurse, but it must be someone you trust. We believe that a coach-led, digital therapy platform is an effective way to not only connect and engage with patients regularly but also improve health outcomes for those grappling with chronic conditions.”

Law 3: Design for the delight and engagement of your end-user.

The US healthcare system has been characterized by poor design choices over a long period of time, which are reflected in the fragmented and highly complex system and the technology that supports it. Studies have shown that poor design is not only driving inefficiencies. In many cases, bad healthcare design is putting patients in harm’s way.

As the healthcare system has become digitized, unintuitive design choices in electronic health records (EHR) have become particularly problematic. Our primary system of record for the industry was designed not to aid clinicians in the daily care delivery workflow, but instead, was created to manage billing.

For every hour of care delivered, physicians spend 2 hours performing record-keeping tasks. When not logging information into the EHR between appointments or late at night after seeing patients—also known as pajama time, which is a big cause of physician burnout—providers are still asked to use the fax machine. Surprisingly, fax facilitates 75% of medical communication, in a world where e-mail, SMS, Slack and other modern communication modalities are the norm in our daily and work lives. Finally, as providers attempt to keep track of the digital and paper workflows running in parallel, they are inundated with alerts and notifications.

Despite the uninspiring state of healthcare design, there is hope. Several trends, including the rise of the digitally native providers and the emergence of strong consumer health brands such as Hims/Hers, Ro, and Nurx, point to the industry and the market’s appetite to adopt simple and elegant design principles in the delivery of highly functional healthcare technology and services.

Regulation can also drive improvements in healthcare design. For example, interoperability rules published recently by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT mandate the adoption of APIs while inhibiting information blocking practices.

What makes the design problem in healthcare more difficult is that care is increasingly delivered in various settings. People receive care in-person, through telemedicine, as well as through text, to name a few. Healthcare design choices must address each of these settings independently while also coordinating across them.

Good healthcare design transmits the right information (evidence-based guidance, response to clinical need) to the right people (entire care team, including the patient) through the right channels (e.g., EHR, mobile device, patient portal) with the right intervention formats (e.g., order sets, flow-sheets, dashboards, patient lists) at the right points in workflow (for decision making or action) with regulation, compliance, security, and ethics in mind.

As for implementing better design practices, we recommend what Dave Hodgson, CEO and co-founder of Project Ronin, shared with us on A Healthy Dose:

“Google’s HEART Framework is a way to measure design performance: Is your product optimized for happiness, engagement, adoption, attention, or tasks success? Many healthcare apps are oriented for task success, such as making an appointment. The secondary metric is around adoption, and ultimately, retention of the patient.”

Law 4: Prepare for slow sales and iteration cycles.

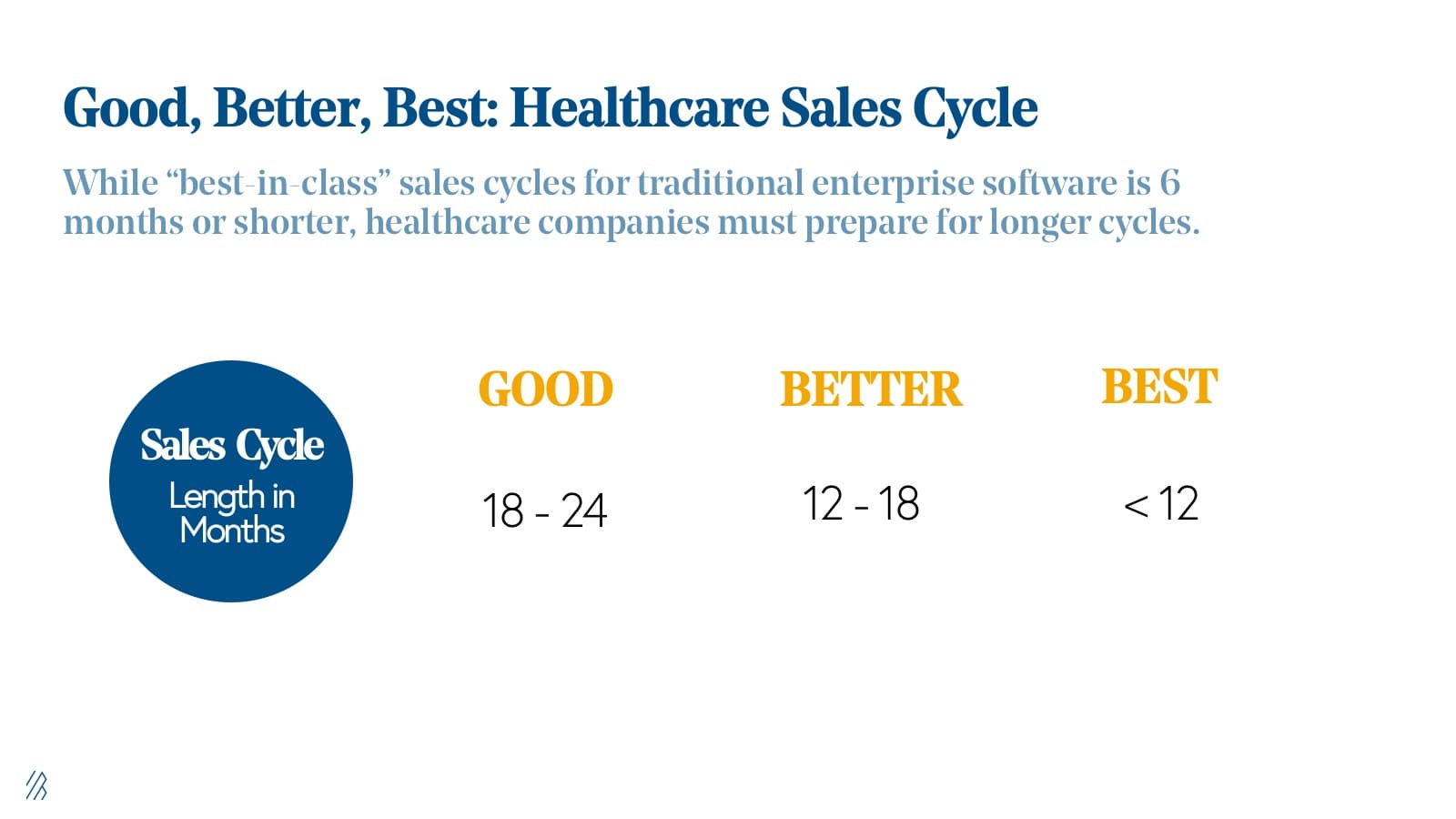

Nearly 60% of healthcare purchases are made after seven months of sales conversations, making healthcare sales cycles notoriously slow. While frustrating for companies, the industry operates in a highly regulated and technologically complex industry governed by the Hippocratic Oath.

Weathering the healthcare sales cycle is as much about validating and demonstrating the need for your company’s offering as it is about hiring the right sales talent. Nothing sells itself in healthcare, but products and services that are solving real problems, eventually, break through the market.

We find that many companies hire expensive healthcare enterprise sales talent before they have exhausted all of their options for getting in the door at health systems and payers.

We recommend to our portfolio companies that they consider a crawl, walk, run approach to product strategy and explore capital-efficient opportunities for validating their sales motion before ramping a sales team.

If almost two-thirds of healthcare sales cycles take seven months, developing strategies to shorten this time to market is critical for all healthcare companies, but most especially for early-stage entrepreneurs. For less mature companies, the cruel reality in healthcare is that it can take up to 12-24 months to close those first sales, to gain referenceable customers, and to build a repeatable go-to-market motion with a scaled sales team.

The more sophisticated and expensive your product is, the more red tape you will have to jump through before receiving a green light. It can be helpful to consider your product’s end goal and work backward not just into a minimum viable product, but a minimum buyable solution that you can provide to your customer while still proving the use case and ROI.

In doing so, consider fewer product integrations, limit the scope of user types, and optimize your budget for the stakeholder who signs off on the purchase. For example, if you suspect that an SVP of Clinical Operations may have budgetary approval for software products that are less than or equal to $50K, you might set your price point at $50K to prevent escalation of your sales conversation to the C-suite. Moreover, this SVP can own the relationship between their organization and your company as you aspire to expand your product, which should solicit a higher contract value over time.

Because of the unique nature of healthcare sales cycles, entrepreneurs must prepare to raise more dollars at the early stage, compared to other venture-backed technology companies. For this reason, we suggest entrepreneurs raise twice as much as they think they’ll need, and assume it’ll take twice as long.

For more advice on how to hire, build, and scale a healthcare sales team, Mark Briggs of Validity, Renee DeSilva of The Health Management Academy, and Steve Kahane of athenahealth share their advice on building and enterprise sales organization.

Law 5: Shorten your sales cycle by demonstrating financial as well as clinical ROI.

One of the most effective ways to shorten sales cycles in healthcare is by generating strong return on investment (ROI) data. More often than not, you are selling to organizations with razor-thin margins, such as hospitals, or those that currently foot the cost of the healthcare bill and would reap any value delivered by savings, such as self-funded employers and payers.

As such, your ROI must be evident and multi-dimensional. The best healthcare companies demonstrate both clinical and financial ROI, which is why they’re concerned about answering the following questions for their prospective customers:

- Clinical outcomes: What impact did the solution have on the clinical outcome(s) of interest?

- Financial savings: What impact did the solution have on the cost of a given activity, such as care delivery or revenue cycle management back-office tasks?

When surveyed, 60% of decision-makers at hospitals and health systems said that they seek to improve clinical outcomes when deciding to purchase healthcare IT; 50% said they try to achieve financial ROI. Our experience at Bessemer tells us that the best tech-enabled healthcare companies hit on both desires; however, we would guide entrepreneurs to optimize for financial ROI first. It is much easier to sell a product that generates $5 for the customer for every $1 they spend on your product.

In reality, it will take much longer to validate clinical outcomes than financial ones, given how research is peer-reviewed. (To be clear, we think demonstrating clinical ROI is the gold standard and will help ensure physician buy-in and satisfaction, which will lead to better retention, potential “word of mouth” virality, and upsell over time.)

The good news is that when a healthcare “pilot” demonstrates financial ROI within the first 12-18 months of deployment, a pilot often converts into a multi-year commercial contract.

We find that financial ROI, when demonstrated within the first 12-18 months, is likely to convert a pilot into a contract, whereas clinical ROI will ensure retention and upsell over time.

Law 6: Healthcare is human. Capture the narratives.

While there are few bottoms-up sales motions in healthcare, patient and stakeholder evangelism is necessary to engage your core market. As such, compelling narratives drive business outcomes, inspire, and drive adoption for decision-makers and patient communities. For example, word of mouth referrals and patient evangelism in the form of online communities and user conferences drive strong retention and increases the likelihood of upsells. (Similar to consumer startups, customer love is a powerful force for healthcare companies, too.) Abridge is a great example of this. The company offers a free mobile app that enables patients to record their conversations with their providers and has experienced strong traction in chronic and rare disease patient communities.

The case studies, success stories, and anecdotes from real people and companies using your service or technology also give team members at a company a sense of mission and helps orient an influential internal company culture. (For example, consider the patient who tattooed Virta’s logo on their body after reversing their Type 2 diabetes through the program. Talk about brand loyalty!)

Source: Virta Health

Of course, not every company is going to get their customers to tattoo their logo on their bodies, but it’s important to showcase patient and user love in authentic ways. While clinical or financial ROI may secure a contract, stories that highlight increased productivity (Law 3), such as taking a headache of administrative work and streamlining it through a software platform, are likely to garner on going support from key decision-makers.

Additionally, healthcare buyers are heavily influenced by what their peers are doing. It is essential to collect stakeholder narratives for use in sales discussions and references. In the health system market, it is common for buyers to visit your customers before making a purchasing decision.

Healthcare companies can greatly learn from consumer brands, or what our Partner Kent Bennett likes to called Consumer Earthquakes, especially when it comes to word of mouth referrals. "Without any paid marketing, do you still grow? We call this unpaid growth rate the 'resting growth rate' (RGR) and it’s the best long-term predictor of efficient growth," he explains below.

A healthcare company’s marketing must share the stories that are backed with data, but also emotionally resonate with their desired audience. When we first met Bessemer portfolio company Groups, which offers medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid addiction, word-of-mouth references made up 57% of Groups referrals and were the most effective form of marketing for driving new member signup. This powerful form of advocacy not only helps grow the service, but also helps people overcome the stigma of addiction knowing that other people are in programs like Groups.

At Bessemer, the companies we remember most are those that have an unwavering commitment to representing the diverse voices of their patients and their stakeholders. These are the companies that inspire us and remind us why we work in the challenging, yet rewarding healthcare industry.

Law 7: Services save lives, software saves time.

Services are the lifeblood of the healthcare industry. We don’t believe that AI is going to replace doctors any time soon, nor do we think there is a viable substitute for human connection.

Tools such as telemedicine and remote monitoring increase access to healthcare services at scale; however, these promising platforms come with considerable limitations, and we must be intentional about how and where we utilize them. For example, most patients would rather learn of a confirmed HIV or cancer diagnosis in-person, not over video. Healthcare providers must use technology to serve patients and serve with sensitivity.

With technology, providers can effectively personalize and serve a wider audience across the four services of the healthcare system, which include health promotion, disease prevention, diagnosis and treatment, and rehabilitation. Today there are dozens of early-stage companies operating across these four areas. In recent years, we have seen an emergence of companies that use technology to provide “full-stack” care (i.e., care across the services continuum) for specific populations and diseases, many of which we highlight below.

There is no single way to marry technology and services in healthcare, though pure-play, tech-enabled, and services-enriched software are three primary ways to deliver better healthcare.

Three delivery models for healthcare services

“Pure play” healthcare services are the types of companies whose core offering is providing services in an in-person setting. These companies primarily utilize technology for practice management, electronic medical record keeping, billing and coding, scheduling, and patient communication. However, we are seeing a few exceptions—many entrepreneurial, upstart companies leverage technology to help improve provider workflow, patient follow up, experience, etc. as well as to provide leverage to their underlying unit economics.

Examples of these types of healthcare services include brick-and-mortar companies such as IVX Health (formerly Infusion Express), Groups, One Medical, Brightline, Cricket Health, Cityblock Health, and non-brick-and-mortar, including Dispatch Health, Ready Responders. As of late, we've found more brick-and-mortar healthcare services offer telemedicine options, especially during the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, we think many of these companies will incorporate virtual care options into their model on an ongoing basis.

Common traits of pure-play healthcare services, include:

- Typically bill through claims or are cash pay.

- Either fee-for-service or fee-for-value

- Typically, clinical staff are employed as full-time employees

- 30-60% gross margin depending on whether there is a B&M footprint.

Tech-enabled services are the companies that provide healthcare through technology or use technology to assist in the coordination and delivery of care. These companies may provide care in-person or remotely (e.g. video, chat, etc.). Telemedicine and telemedicine-powered services fall in this category.

There are four subsets of tech-enabled healthcare services, including employer-facing (e.g. Hinge Health, Livongo, Omada, Ginger, Lyra), payer-facing (e.g. ConsejoSano, Cogitativo, Embold Health), pharma-facing (e.g. Verana Health, RDMD, Evidation Health), and consumer-facing (e.g. consumer-facing: Ro, Hims, Nurx, Curology, Folx Health).

Common traits of tech-enabled services, include:

- Clinical staff typically employed as 1099’s

- No brick-and-mortar footprint

- Bundled services into a recurring fee, such as PMPM, or per unit (e.g. per query if a data services business).

- 50-75%+ gross margin

Services-enriched software companies, such as CentralLogic, Qventus, and Kyruus, sell software and utilize services during implementation and client support to bolster their offering and drive stakeholder alignment, change management, and adoption.

Common traits of services-enriches software companies, include:

- Deployment via on-the-ground implementation and for ongoing service

- Charge implementation fees

- Subscription licenses based on a unit function

- 65%+ gross margin

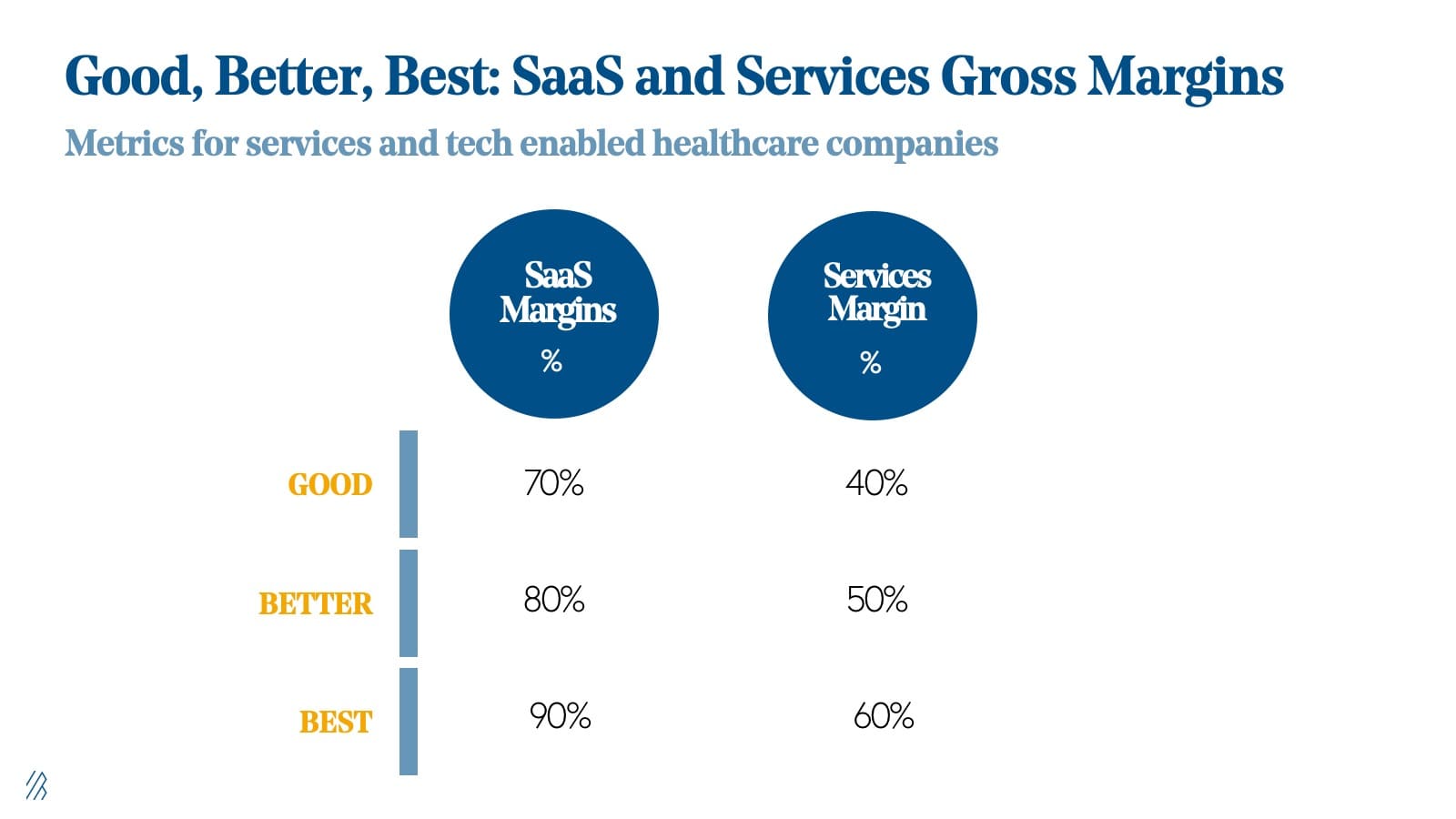

We believe most healthcare tech companies also need to include service offerings, and therefore blended gross margins in the industry are lower compared to other technology industries we traditionally invest in at Bessemer. Here is our healthcare team’s view on a framework to think about various gross margins for healthcare technololgy companies.

Law 8: Capitalize on outsized LTVs.

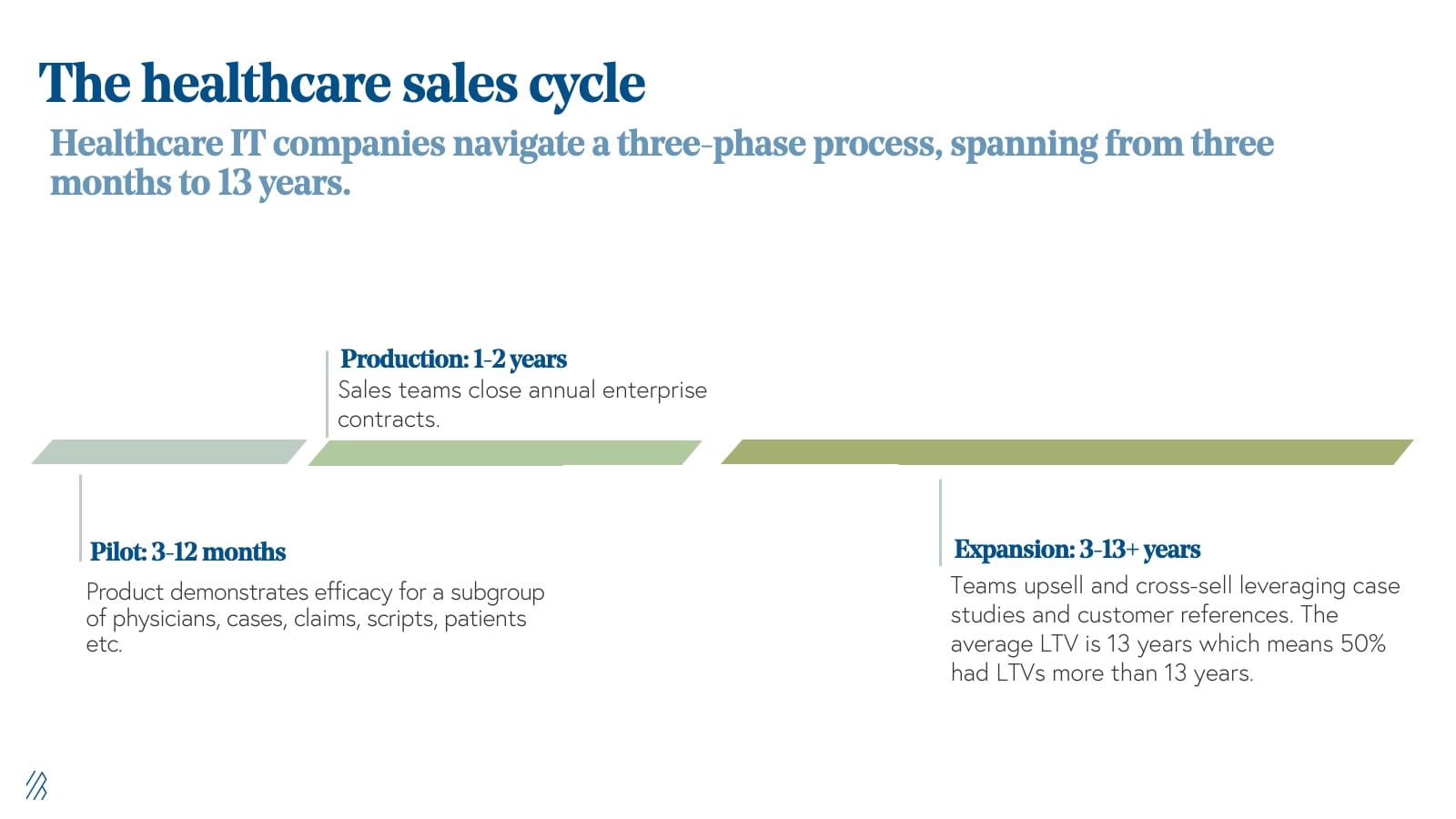

Whether selling to providers, payers, pharma, or even self-funded employers, the healthcare sales cycle is notoriously slow. A long sales cycle, coupled with the high costs of supporting an enterprise healthcare sales team, sounds like a recipe for a capital intensive venture. While there are no shortcuts in healthcare sales, weathering the rigorous enterprise sales process using the tips we outlined in Law 4 can pay handsome dividends on the other side.

With an expensive and less cheerful sales cycle than other industries, it’s helpful to remind healthcare leaders of the favorable deal dynamics in healthcare. Multi-year contracts for six to seven figures are industry standard, and pilot engagements, which often span just a few months to a year, can be worth six figures.

Healthcare may be slow to buy, but the industry is equally slow to churn. Several years ago, Bessemer analyzed healthcare IT companies that went public and found that the average LTV was 13 years!

For most successful HCIT companies, they’ve gone on to navigate a three-phase process, spanning from three months to 13 years.

- Pilot (3-12 months): Product demonstrates efficacy for a subgroup of physicians, cases, claims, scripts, patients etc.

- Production (1-2 years): Sales teams close annual enterprise contracts for an entire department, system, or patient population.

- Expansion (3-13+ years): Teams upsell and cross-sell providers, sites, payers, plans etc. leveraging case studies and customer references. It’s important to not that for Healthcare IT companies the average LTV is more than 13 years, which means that 50% of these companies had LTVs more than that.

Law 9: Make regulation an asset, not just a liability.

A single regulation could unlock a multi-billion dollar healthcare business opportunity. With that in mind, S-1’s of nearly every publicly traded healthcare company mention regulatory risk. Not only are healthcare companies subject to the typical uncertainties of market forces, but they are also quickly impacted by the political climate and regulatory changes.

We believe that over-investing in regulatory and compliance, especially early on in a company’s journey, is essential in healthcare and is more important than ever today.

Over the last few years, we’ve seen what happens when companies get it wrong (e.g. Theranos, UBiome, and OutcomeHealth). Unfortunately, these companies were not only enormous disappointments for the industry at large, but they’ve driven increased skepticism (and fear) around innovation among healthcare incumbents.

However, we’ve also seen many companies get it right by viewing regulation as not just a risk, but also an asset. Regulation can drive product innovation, generate RFPs, build a competitive moat, and instill a sense of urgency to close a sale and implement necessary solutions.

Over the long term, regulation can be a category creator. Consider the HITECH Act, a law enacted in 2009 to promote the adoption and meaningful use of health information technology. Studies have validated that the meaningful incentives created by the HITECH Act drove a dramatic increase in the adoption of EMRs over the last decade, having grown almost 7x since the law was enacted. This regulation paved the way for Epic, Cerner, athenahealth and the plethora of other certified EMR vendors to scale rapidly in the market as well as hundreds of third party software companies that interface with these systems of record.

We anticipate that the COVID-19 pandemic recovery period will present several new regulatory changes that not only better position our system to respond to future viral outbreaks with speed and agility, but that also catalyze opportunities comparable to those enabled by the HITECH Act and recent ONC Interoperability Ruling.

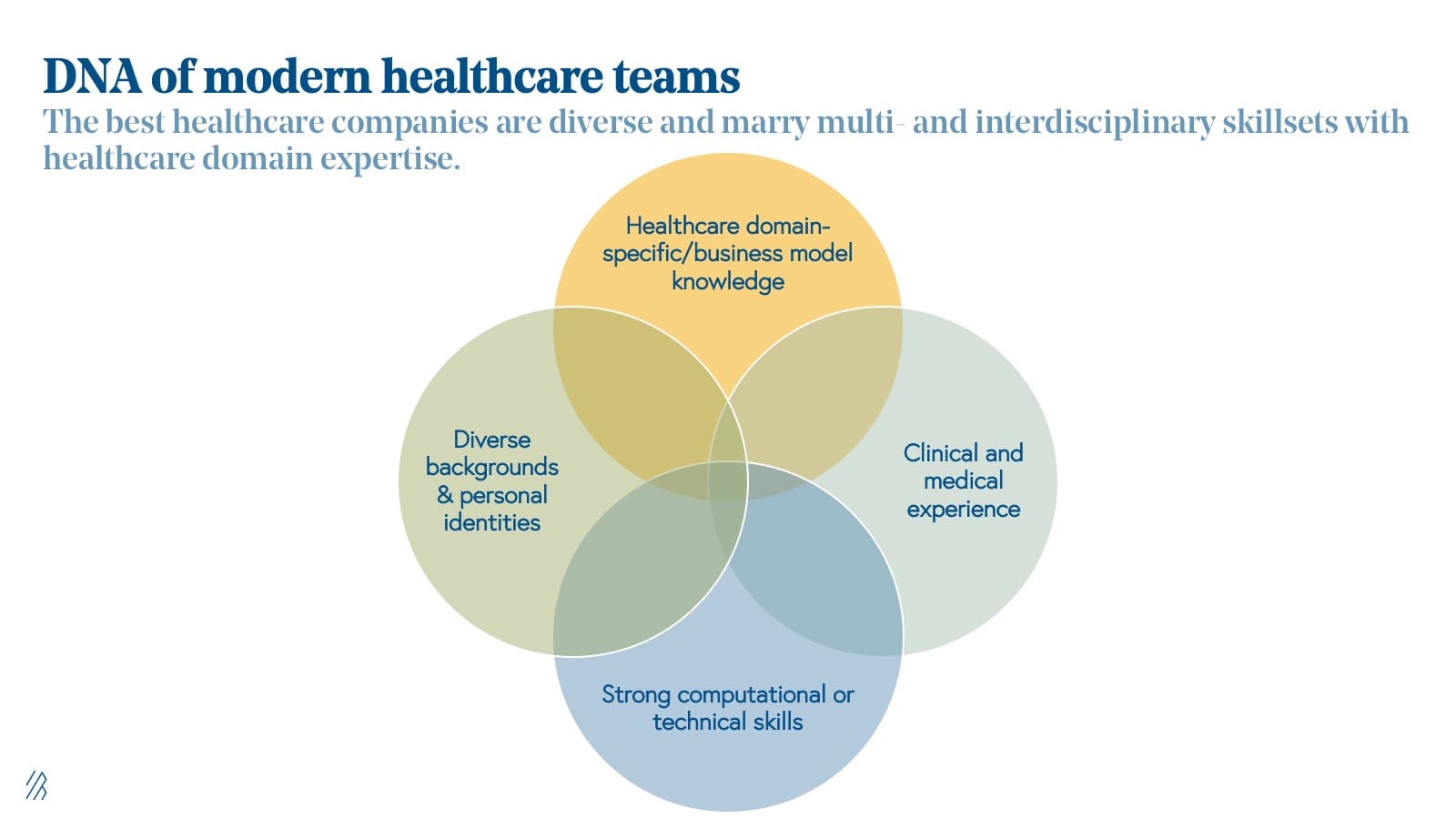

Law 10: Diverse, multilingual teams win.

Diversity matters in healthcare and takes many forms. The best companies marry teams built by executives from diverse backgrounds with cross-disciplinary and mission-oriented talent. They are “multilingual” in that they speak business and technology (and offer their services in many languages as well), but also speak the language of their customers, patients, and key industry stakeholders.

For example, Bright Health is a Bessemer-backed unicorn looking to transform the traditional insurance model by eliminating friction between payers and providers, while driving down costs and improving health outcomes. Their team includes 12 CEOs, including the former CEOs of UnitedHealthcare, Optum, and Magellan Health, as well as leaders from tech companies like Google and athenahealth. It also includes former C-suite executives from leading consumer institutions such as Target and Best Buy. Bright Health’s fundamental disruption is their ability to marry best-in-class consumer experiences with a strong design for healthcare plans and distribution.

“The most disruptive companies over the next few decades will build multi-disciplinary teams,” said Bob Sheehy, CEO of Bright Health. “They will leverage the lessons learned across industries to make healthcare, as a relationship, stronger.”

In another case, Insitro, a computational drug development company, implements cutting-edge machine learning techniques in the life sciences industry. Insitro’s fundamental disruption is the integration of computation and biology across the company from data generation and collection to molecule development. To do this, Insitro hires “multilingual” talent fluent in the rigorous mathematics behind machine learning and advanced computation as well as wet-lab biology and pharmacology.

When we speak with early-stage healthcare entrepreneurs, we want to see that their management teams have a breadth of experiences across tech, healthcare, and deep clinical experience.

Finally, we all have "health," and as a result, management teams and caregivers must reflect the diversity of the populations they serve. A diverse team is integral to providing equitable care for all patients. In response to the system’s historic inability to serve marginalized and minority patients effectively at scale, more companies are emerging that focus on serving the needs of these populations specifically. For example, Folx Health, a direct-to-consumer queer health and wellness platform focused on the LGBTQ+ community and a Bessemer portfolio company, has hired Queer-identifying clinical leaders and technologists to position the company to best support their patients. Healthcare companies must prioritize hiring and cultivating teams that have these multidisciplinary skills and backgrounds while also ensuring that people from different backgrounds, including gender identity, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation, influence decisions on how to provide more comprehensive care.

Bonus Law: Build for a value-based world.

We expect 2021 to be a massive year for value-based care as we nurture the system back to health and begin pandemic recovery. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has released several value-based care programs available to providers and payers that are increasingly contracting with new care management companies across primary care, renal, and maternal care, in particular.

While just over half of the payments made to providers in 2017 were value-oriented (e.g. tied to performance or designed to cut waste), an overwhelming majority of these payments maintained a fee-for-service (FFS) foundation according to the 2018 National Scorecard on Payment Reform.

As of 2017, only 6% of total commercial dollars came from a value-based payments model with downside financial risk, and payments made via bundled payments models have remained relatively flat since 2012.

Before we make this transition and evolve from voluntary-based incentive models to a world where value is mandated, more systems and institutions need to adopt this new paradigm. Today there are still existing resource constraints, gaps in interoperability, and looming concerns around the unpredictability of revenue in value-based models.

We encourage founders and executives to ensure that companies continue to support products, business models, and customers in the fee-for-service world today, but that they strategize for tomorrow and build for value-based care

“Trust is the thing that unlocks the door to the outcomes and attributes in the [value-based] system we want to build,” said Toyin Ajayi, Chief Health Officer at CityBlock Health. “By systematically asking about social needs and non-medical health-related drivers, and following the logical threads of those answers, we can deploy and prioritize interventions, coach behavioral changes, and champion healthcare resources for better outcomes.”

We’ve been talking about value-based care for years, and our energy and investments are gravitating toward this transition more so than ever before. The global pandemic has been a watershed moment for many fast and necessary changes in healthcare; COVID-19 has demonstrated that the FFS paradigm isn't a sustainable model—hospitals were busier than ever but losing $50 billion per month. Much like the transition to the cloud was a calculated, yet worthy risk for enterprises to pursue two decades ago, we believe moving toward value-based care systems will yield massive business outcomes and systematically improve the wellbeing of diverse patient populations for years to come.