A brainstorming framework for aspiring founders

Four stimulating questions that can help entrepreneurs overcome their mental blocks and hang-ups as they decide on a new idea for a startup.

Pattern recognition is a natural human inclination, but the paradox of venture capital is that investors are at their best—and their worst—when they rely on this cognitive skill. After interacting with a high volume of startups and founding teams, the urge is hard to resist as I see recurring patterns in how founders explore and consider new opportunities. Throughout my venture career, I’ve found framework-thinking a critical part of assessing investment opportunities. While founders, like artists, likely bristle at the idea of being classified, they too can leverage frameworks to brainstorm startup ideas to illuminate the many paths open to them and give them a greater sense of confidence in the path they ultimately choose.

The founders I interact with at this embryonic stage are typically second-time entrepreneurs and highly entrepreneurial individuals who are determined to create their own company and yet wise enough not to rush ahead with the first idea, or even the best idea at present. My role as an early stage VC is to challenge their assumptions and serve as a convenient, impartial sounding board that can weigh-in as they toss around ideas and directions.

This brainstorming framework is built around four core questions aspiring founders must consider throughout the process of startup ideation and creation.

*Asterisk notes Bessemer-backed companies.

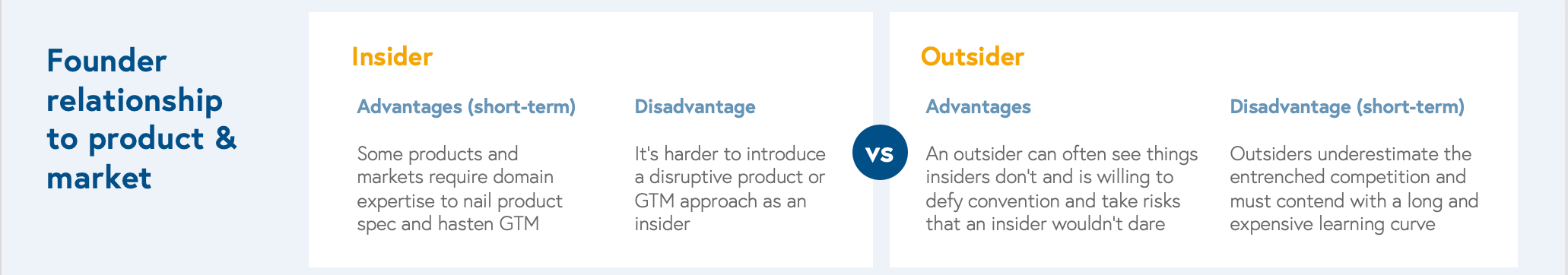

1. A founder’s relationship to product and market

Do you seek to solve a problem you know well as an “insider” or solve someone else's problem as an “outsider”?

The instinct of many founders is to address a problem they’ve personally experienced and dealt with before. It's tempting to lead with this because your familiarity with the problem generates immediate passion and conviction. You know enough to start working on a product spec and are able to move fast and deliberately. As an “insider” you are approaching the problem as a confident expert, which can give you a powerful edge when pitching investors and engaging customers.

The quintessential insiders are founders who’ve dealt with the problem they are trying to solve at their prior company and want to bring a solution to the wider market, such as the founders of LaunchDarkly*, PagerDuty*, and Axonius*. Having encountered the problem in their former roles, insider founders can speak to prospective customers as peers, which lends immediate credibility. The insider approach is most common among technology and infrastructure software startups, where founding CEOs usually have a technical background, but there are notable outsider exceptions.

Among application SaaS companies, there are several types of insider founders. One is a founder who previously worked in non-tech companies from the same sector, giving them a unique insight into the customer needs, such as the founders of ServiceTitan* (home service trades), Papaya Global* (global payroll), and Optibus* (public transportation). Others cut their teeth solving customer problems as an outsourced software service, including the founders of Zendesk, Jfrog, and Cloudinary*. Yet another type of insider are founders who, having previously worked at a company addressing the same problem, now see an opportunity for a “next generation” product to make a bigger impact, such as the founders of Zoom, Docusign* and Forter*.

The primary disadvantage of being an "insider" is that you are less likely to think “out of the box” and challenge prevailing assumptions in both the product and go-to-market (GTM) strategies. And the worst part of this is that you likely won’t realize it until an outsider arrives on the scene with something wholly disruptive.

Outsiders are akin to immigrants from a distant land. Immigrants often find success in a new country because survival requires that they be observant, skeptical, and innovative. So too can the industry outsider find success in a sector he or she has never considered before. Being an outsider in an established sector can be daunting and discouraging, but many successful startup disrupters came at the opportunity as underdogs and interlopers. Founders arrive in a new domain not merely out of curiosity but because they are fatigued with their area of expertise and lack the requisite passion to start something new in the field.

Since outsiders aren’t experts that know the proverbial rules of the game, they tend to approach both product and the GTM in ways that insiders either wouldn’t consider or wouldn’t dare. As an outsider you are blithely disobedient and non-conformist, if not naive. And naivete can be a key strength for the outsider founder provided you are self-aware and endeavor to learn fast and continually iterate. Outsiders believe expertise is overrated but are still relentless as they ascertain the opportunity as they rapidly become an expert in their own right.

A common outsider approach is to address a problem the founder has personally experienced as a client of their target customers, but in a sector in which they know very little. The founder of Procore* didn’t come from the construction industry but he had indirectly experienced the industry’s pain when struggling to manage the construction of his own home. Other prominent examples of founders solving a problem they personally encountered as customers include Shopify*, Intercom*, Canva*, Pipedrive*, VTS*, and Dropbox. These outsiders channeled their frustrations as users into a product that would benefit everyone else. Student founders are almost always going to be outsiders given their limited work experience, but even experienced founders sometimes choose to disrupt as outsiders. At the inception stage, the founders of both Toast* (restaurant POS) and Hibob* (SMB HRIS) were, to a large extent, ignorant of their respective sectors when they set out to transform those sectors and that was a key advantage.

At the same time, hubris and impatience have doomed many outsider founders given what is often a long and expensive learning curve. You may underestimate the competition, the depth of the product challenge or the obstinacy of the customer base, which means much more time and capital is required. As an outsider, the investors you pitch may be skeptical of your ability to win and even dismissive if they consult “industry experts.” When attempting to solve someone else's problem, the key is not fooling yourself into thinking you already have the answer merely because you are a frustrated customer or an experienced entrepreneur. The best entrepreneurs find creative ways of closing the knowledge gap as Melio* did by running their own bookkeeping service or as Canva did by operating a yearbook business to test the usability of their design product.

Sectors already undergoing change are uniquely suited to penetration from outsiders who see an opportunity to accelerate that change and dislodge idle incumbents. This has been the case for many of the most successful fintech and payments success stories from Stripe and Square to Plaid and Melio. Vertical SaaS is another sector where outsiders have been able to quickly overshadow incumbent vendors whose products are outdated and unimaginative. Among SMB SaaS companies it is also common to see founding teams from outside the industry—examples include, the founders of Gusto in payroll, TripActions in travel management and Monday in project management. And as mentioned earlier, outsiders can also excel in technology infrastructure with examples including Tanium and SentinelOne in cyber security, SolarEdge in cleantech and DriveNets in routing.

There is a third type that falls somewhere in between the insiders and outsider archetypes, which is an outsider with a personal network of insiders. These founders focus on a problem they know nothing about, but in a domain in which they are already well connected. Since this is not their problem they can’t immediately get to work as an insider might but they know enough customers who’ve experienced this problem thereby accelerating their learning curve, while preserving the outsider advantage.

Not all startups fall neatly in this insider/outsider dichotomy and some founding teams may include a combination, such as a CTO insider and CEO outsider, or vice versa. The key takeaway is that founders have full agency to choose whether they want to pursue something as an insider or outsider, or something in between. The power comes from the self-awareness of the archetype and how that can inform future decisions.

There is an additional angle to the insider/outsider consideration that relates to skill sets rather than industry/sector expertise. For instance, a founder with a strong background in enterprise field sales will feel in foreign when building a low-touch sales model for SMB despite remaining in the same sector. And a product-oriented founder with vast expertise in UX/UI will naturally feel a need to develop a product that leverages this expertise. The ”insider” in both cases feels a need to play to their strengths and experience versus developing new ones.

As a founder you must not fall into the trap of pigeonholing yourself based on memorable founder stories that are top of mind or that will make for a nice headline once successful. I’ve seen founders become passionate about opportunities they only learned about yesterday, so you owe it to yourself to explore. The charming idea of “founder-product-market fit” sounds insightful but is largely a retroactive observation of little substance, much like the notion of one’s destiny. The reality is that great founders can pursue ideas that belie their resumes and personal experience, and one’s background (or lack thereof) shouldn’t be seen as an impediment.

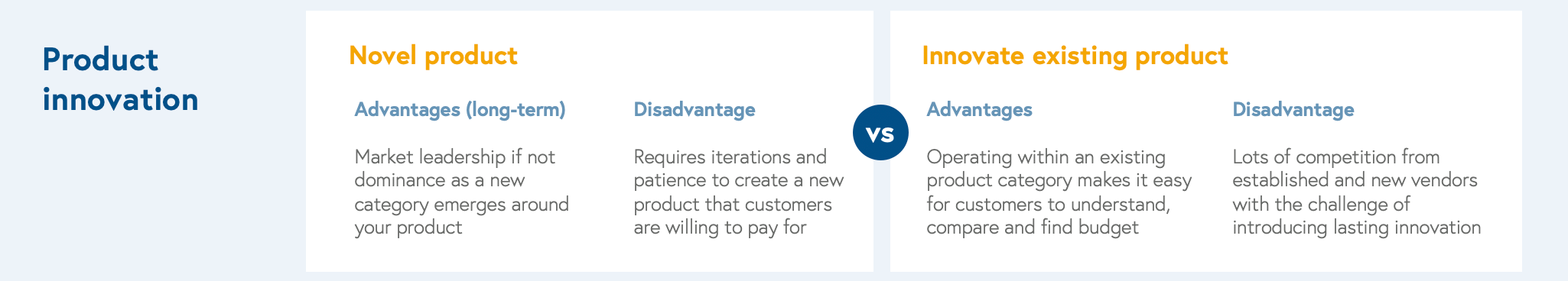

2. The extent of product innovation

Do you innovate in an existing product category or attempt to create a novel product category?

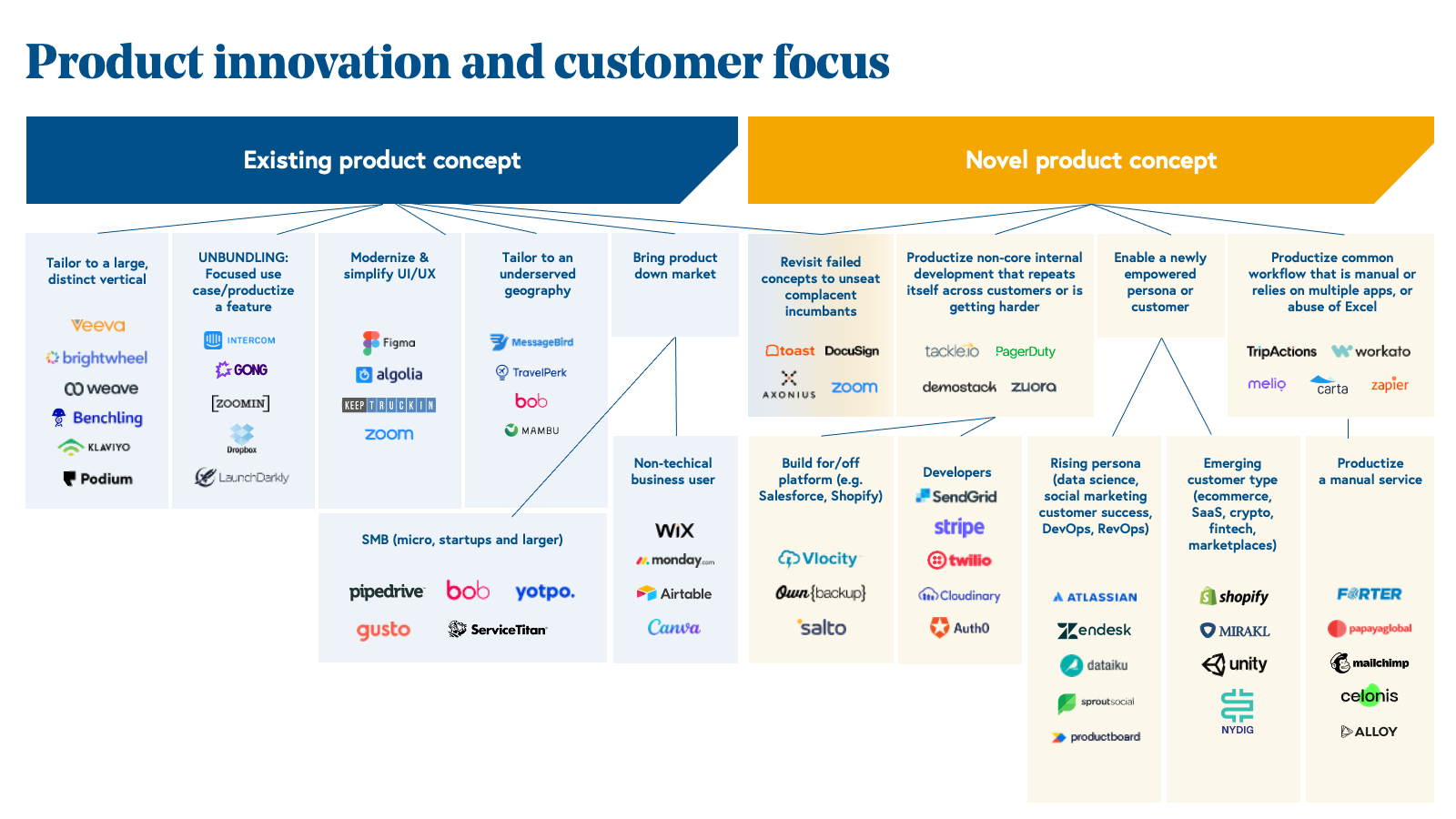

Innovating in an established product category has the advantage of a buyer intent and budget, a clear yardstick for competitive comparison, and familiar sector messaging and nomenclature. The purpose and value of the product to customers is well recognized thereby easing the sales and marketing motion for new entrants and their sales and marketing teams. The opportunity for a new startup in an existing product category is one of challenging the incumbents head-on or expanding the customer universe beyond those customers currently addressed. Attacking slow and complacent incumbents is most common during times of technology transition, such as the move to cloud or mobile, but also when the market leaders have become too big to properly address their diverse customer needs.

Startups can find a wedge by modernizing a clunky user experience , productizing a key feature in a bloated product, or combining core functionality from different products that saves customers time and money (e.g. Dropbox, Wix*, Canva). Other startups choose to focus on a neglected subset of customers, especially those with unique or diverging requirements including specific industry verticals (e.g. Veeva, Klavyio) or geographies (e.g. TravelPerk, MessageBird). And yet other founders find a way to build a product that is more appropriate for SMB customers and better suited for a high velocity, low-touch sales model (e.g. Pipedrive, Yotpo*, Intercom). Of course, even modest product innovations can beat the competition head-on provided it is combined with innovative go-to-market innovations (e.g. Zoom, TeamViewer*).

The disadvantage in addressing an existing product category is overcoming the inertia of customers where the competition is entrenched, combating the noise of other competitor upstarts, and underestimating what it takes to reach minimal feature parity with the competition. Beyond myriad product features, matching the competition often includes support for third party integrations, advanced enterprise features (collaboration, security, reporting), and some level of professional services.

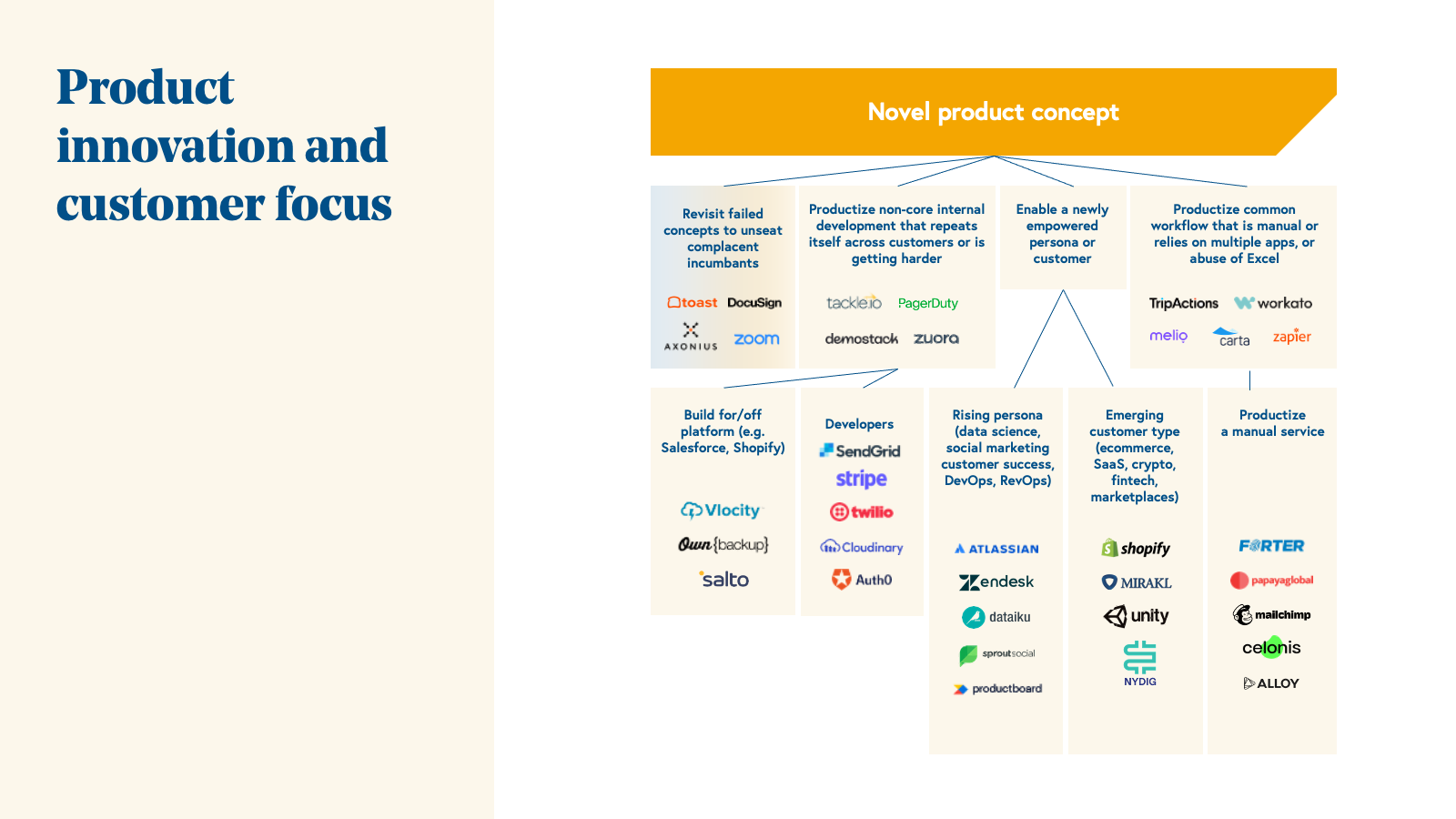

Wary of going head-to-head with industry giants, it is unsurprising that many founders are attracted to the allure of creating a “novel” product category with the potential for unimpeded growth and uncontested market leadership. Novel product categories rarely emerge from scratch and there are often precursor product concepts that light the way for founders and customers alike. For instance, astute founders will often focus their sights on an internal development effort that repeats itself across the ecosystem signaling an opportunity for a commercial off-the-shelf product. Many developer-focused startups emerged from this observation, including those in code management (e.g. Github, Atlassian), security (e.g. Auth0*), payments, billing, messaging and data management. In other cases, novel product concepts arise from productizing an existing cumbersome workflow or business process that relies on manual work or a mishmash of outdated technology solutions. Examples include Alloy* in KYC, Forter in fraud detection, TripActions and Papaya Global in remote payroll, Basis Theory* (data tokenization) and Checkr (background checks).

Another common opportunity for product category creation is found with the emergence of fast growing customer segments such as D2C ecommerce, fintech, marketplaces, crypto, and SaaS. As distinct tech verticals with unique needs, targeting customers in a segment offers the potential to catch the same wave of growth and excitement that has lifted them to great heights. A related opportunity is to focus on products for a newly empowered persona or a department in the organization that has gained greater autonomy and budget to achieve their goals (e.g. DevOps, RevOps, HR, CS, data science). For instance, a lot of “no-code” product ideas cater to newly empowered non-tech users within the organization (e.g. Zapier*, Intercom, Airbase).

The disadvantage of a novel product category is in the indeterminate amount of time and effort required to build a product spec that customers cannot easily grasp until they use it. Without a customer budget and with unproven customer value, it can be a real uphill struggle. Even when there are signs of product fit, the market can turn out to be surprisingly small. Companies attempting to create a novel category are advised to be conservative with their expenses until there are irrefutable signs of product-market fit and customer traction.

Of course, some of the examples in the charts above are companies whose products could be placed in more than one category. (Recall that this is a framework for brainstorming new ideas, not a taxonomy for established businesses.) It should be noted that some plans start as novel and back into more established product categories as they grow. Other plans start in an existing category but introduce enough innovation over time to effectively create a new product category (e.g. Twilio*). Regardless of what you choose there will always be tension between building a product that you believe in and solving a customer pain point as I’ve detailed in the product-market journey.

3. TAM vs. focus

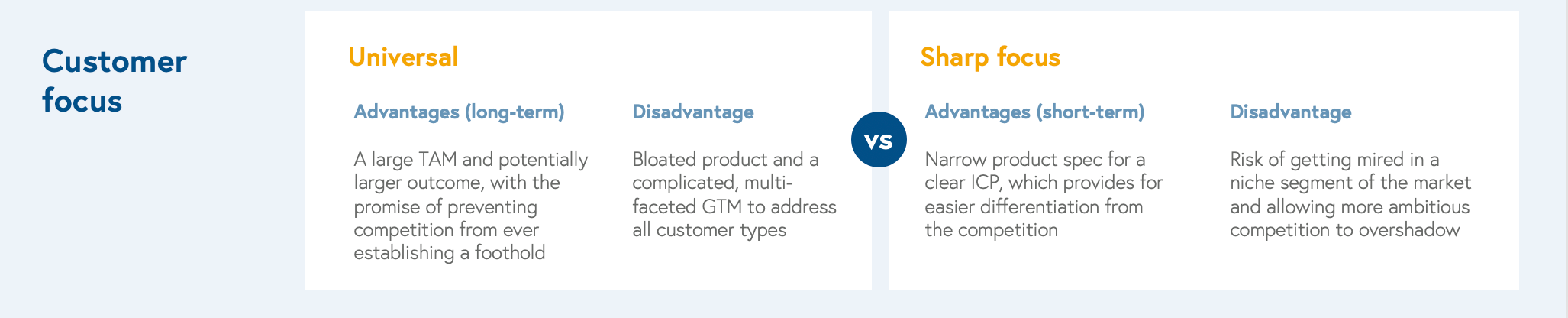

Do you favor a widely applicable product with a large market, or focus your product on a smaller, well-defined customer segment?

Intuitively, founders know they need to demonstrate a large TAM to entice investors and that’s true especially if you need to raise a lot of capital. However, investors also know that attempting to make a product universally applicable may result in a product that is not a great fit for any customer. Unsurprisingly, investors want a large TAM as well as focus, which is why the most effective product plans strike a balance by focusing on a growing subset of a large market.

Customer focus enables a startup to better define the product and build the appropriate GTM strategy for that customer segment. There are various ways to narrow focus including customer size by revenue or headcount, by industry vertical or geography. In other instances, focus may involve targeting customers with a certain technology stack or customers with a specific buyer/user persona. The product should be tailored to your ideal customer profile (ICP), but relevant to those outside of that ICP profile. At the same time, you should also have a good sense of the types of customers you will not focus on or sell to.

It is a curious fact that founders and investors alike find a way to make any market look big enough to justify the investment. The reality is much more complicated as large markets are harder to penetrate and with enough patience non-existent markets can emerge overnight as massive new market opportunities. The more sober your assessment of the true addressable market, the better prepared you will be.

There is nothing wrong with targeting a specific market segment that investors may perceive to be too small as long as your fundraising and spending plans aren’t a mismatch for this smaller opportunity. Markets can evolve rapidly and what was once dismissed as too small can later be revealed as one of the largest market opportunities.

A final piece of advice I give founders related to market focus is to choose their customers wisely, not unlike they might choose their investors. You must have a genuine interest in engaging with the customer but also a conviction in your customer’s future. It’s a very long-term commitment you’re undertaking, and you can’t easily divorce yourself from your customers, so if you don’t like interacting with them, consider a new problem to solve.

4. Riding macro trends

Do you jump on the bandwagon of a “hot trend” that has investor attention or pursue something under the radar and longer-term?

Macro trends help build conviction that the status quo is untenable and if you don’t build it someone else will. They lend support to any startup pitch by providing justification for the inevitable question of “why now?” This is a compound question that probes whether customers are ready to embrace change and what facilitates the product innovation you are pitching. In considering this question, many founders focus far too much on what is now technologically feasible, neglecting the broader market, product and customer trends.

Macro trends include cutting edge technology developments, but also secular business and economic trends. Since most customers buy products, not technology, there is usually a business consideration driving the decision to purchase that is unrelated to the underlying technology that addresses the problem. Too many founders start by thinking of a challenging and intriguing technology trend and the problem they can solve with it, when they should be starting with the problem. Startup success has more to do with timing than technology, which is why business trends generally outweigh technology trends.

Examples of long-term technology trends include the move to cloud and mobile or the use of automation technologies such as AI/ML. More recent technology trends can also work but carry the risk of being hype or difficult to monetize. Another type of technology trend may be the anticipated commoditization of an expensive technology which will enable something that was previously price prohibitive.

A long-term business or economic trend can provide wind in your sales for the foreseeable future, easing the GTM motion, fundraising, and recruiting. However, if it’s a short term trend (like a recession or pandemic), not only will the impact prove fleeting, it will likely cause a distraction and lead to poor decision making. Long-term business trends may revolve around innovative pricing and payments (e.g. freemium, subscription, usage-based payments), changes in who has purchasing power or changes in who increasingly uses the product (e.g. employee, developer, SMB). Long-term economic trends may include industry digitization, international commerce, e-commerce, remote work, the changing employee/employer power dynamic, remote health, food scarcity/environment, or cyber security risks.

When considering a new product idea, a lot of founders start with macro trends, because they appear prominently in headlines about other startups that raise money. This is a problem because founders tend to conflate fundraising success with market validation. Positive investor sentiment can be an encouraging signal, but it will never be as compelling as positive customer sentiment. Founders should think foremost what customers are willing to pay for and only then figure out how to position it to investors in the most favorable light. Investors always notice customer traction, but customers don't care about investor traction.

The thrill of a new beginning

I love the brainstorming stage because it allows me to vicariously experience the thrill of startup ideation and creation alongside founders. There are many more topics to consider from capital needs and gross margins to pricing and distribution models, but in considering these four questions, founders can begin to narrow their focus by ruling out certain paths. Regardless of the path chosen, it should be comforting to know there are others who have taken a similar journey with familiar challenges and risks that await.

*Mentioned Bessemer-backed companies, A-Z: Auth0, Axonius, Canva, Cloudinary, DriveNets, Hibob, Intercom, LaunchDarkly, Melio, Optibus, PagerDuty, Papaya Global, Pipedrive, Procore, ServiceTitan, Shopify, TeamViewer, Toast, Twilio, VTS, Wix, Yotpo, Zapier.